Did I Do Enough?

CHAPTER SIX

TARAWA 1943

EDITORIAL NOTE: In March of 1994, I received a letter from Colonel Joe Alexander, a retired Marine. He was writing a book for the Naval Institute Press on the battle of Tarawa and wanted my account of the battle. Colonel Ed Driscoll, a longtime friend and fellow Marine, had given him my address. At that time my wife Gladys and I were in Mesa, Arizona, where we had been spending winters as "snowbirds" since 1990. Having no word processing capability with me, I wrote Joe a brief handwritten account of some of my most vivid memories of the operation and promised him a more detailed account upon our return to Puyallup, Washington in May. The following letter dated 29 June 1994 to Joe is as good an account as I could muster on a combat experience I had some 51 years earlier.

"Dear Joe - Please excuse my tardiness in responding to your request for my account of the Tarawa battle. I was not the radio chief for 2/8 (2nd Battalion 8th Marines), but I was a sergeant, having been promoted before we left New Zealand in a regimental wide competitive exam. We received both promotions in 2/8 of the two available with wireman Dick Hogue getting the other one. I was in charge of the TBX team (the TBX was a three man radio set used by Marine Corps units to participate in unit to unit communications) scheduled to operate on the Regimental Command Net with the 2nd Marines. As I recall and you probably know (from your 30 months of research), 2/8 was attached to RLT-2 (Regimental Landing Team 2) for the landing. I believe my landing craft was in the second or third wave (after the amphibian tractors of course). My best buddy, James B. Martin from Springville, Alabama (later was Postmaster there) had our other TBX (two TBX's per Bn (Battalion) as I recall) and he was on a Naval Gunfire Spotting Net with some direct support ships. To the best of my knowledge, Jim and I had the only TBX's operating on the island.

Of course everyone is familiar with the stories of landing craft literally sinking from under them. My experience was no different. We were an estimated 800 yards from the beach when the landing craft opened its ramp and off we went. As I stepped off the ramp, I was barely able to touch bottom and sort of bounced along for some time. There was a great deal of mortar and small arms fire, but I remember being rather oblivious to all the racket. I only had one thing on my mind, which was to get to the beach and get our TBX on the air. Of course I also wanted to survive, so as a friendly tank lumbered past, I grabbed onto the rear and hung on.

On the way to the beach I encountered our Battalion Communication Officer, a newly appointed second lieutenant named Kern, Kearny or something similar. He had been hit in the leg, and was bleeding profusely in the water. He was heading back to a landing craft for evacuation, and I asked him for the authentication tables for days D+1 and thereafter. (Authentication tables were used to verify that you were who you said you were). I was only carrying the D-Day tables. He refused to give them to me--I don't know why. In any event, to my knowledge we never found out what happened to him.

We were landing just to the left of the long pier that jutted out into the water. On reaching the beach, we located what apparently was an abandoned mortar position not too far from the end of the pier--perhaps within 50 yards or so. It was open on the water side, about 12 feet by 12 feet and perhaps 5 or 6 feet deep. The sides were of logs on three sides and it opened into a covered bunker on the land side of the position. It appeared to be an ideal position to set up our TBX. I had two PFC's, Clarence Backus from Danville, Illinois and "Eddie" Fisher from Texas. The only problem at the moment was that Backus was missing. So after removing the transceiver case from my back, I proceeded to run up and down the beach looking for him.

As I recall he had the accessory case, which of course was an essential element, since it contained the receiver batteries, the headphones, microphone, telegraphic key. connecting cables and other items necessary for operation of the radio. I located Clarence lying behind the seawall a few yards (perhaps 25-30) from the water's edge. He had been shot (appeared to be 25 caliber) in the neck with an entry and exit wound on each side of the neck. (He was still alive.) I retrieved the radio accessory box from him and hailed a passing Marine to help me get him into a landing craft for evacuation. As we began to walk him toward the water, a burst of automatic fire started kicking up sand around our feet. I began cursing the unknown weapons wielder and then glanced over at the "Marine" assisting me only to discover it was the Battalion Chaplain. I started to apologize for my language, but he assured me that he understood, and that in fact he had been thinking similar thoughts.

After getting Backus safely on board a landing craft for evacuation, I ran back to the dugout where we would set up the TBX and get on the air. After setting up, I started calling Regiment. It was a CW (continuous wave or Morse code) net (not voice) and after several frustrating and fruitless attempts to raise Regiment, I finally heard another station answering me. Not recognizing the call sign, I learned through the call sign extract card I had in a waterproof pouch that the unknown station was actually Division Headquarters (aboard the battleship Maryland) trying to establish contact with anyone on the beach. I was pretty happy to have contact with anyone. We had telephone contact with Regiment (2nd Marines) and I advised Division that we would relay messages to Regiment via landline.

I contacted the Regimental Communication Officer by telephone and advised him of our contact with Division and that we would act as a relay for any messages they wished to send. The Regimental Communication Officer, a Major, then asked if I could move our TBX down the beach to where the Regimental Headquarters was located. I was not thrilled by his request but believe that I might have complied if he had insisted. I did advise him that we had already had one wireman killed on the edge of our bunker and that I could not guarantee that we could make it to his CP (Command Post) carrying the TBX. As I recall the Major was satisfied, so long as we could keep the wire line in to him. I did not remind him that communication between higher and lower headquarters was the responsibility of the higher unit. The wire line stayed in and I relayed all the traffic between Regiment and Division for all three days of the battle. To the best of my knowledge, my TBX had the only contact with Division Headquarters during that period.

On the second day of the operation, Division challenged my use of the authenticator tables. I had continued to use the first day table since I had no other. You will recall that the Battalion Communication Officer had turned down my request for them in the water. I believe he thought that he would be able to get his wound attended to and proceed back to shore. After several futile attempts to explain my problem using various operating signals (in Morse code), I finally asked Division to switch to voice. They complied and I must assume that my Louisiana accent convinced them that I was authentic enough. After all, I was all they had. We switched back to CW and continued to pass messages back and forth.

My only problem was getting someone to give me some relief on the set. Backus of course had been evacuated, and Fisher had developed a disabling headache--very severe. He remained ill for most of the operation. So my watch turned out to be some 70+ hours long. I did get other people to spell me during periods of inactivity, but they would call me as soon as they heard a signal on the air. Wiremen were operating the hand generator for me and it just became something I had to do. As far as I can remember, I did not eat a bite of food for the full three days. I had two full canteens of water and only a few swallows of water was gone from one of the canteens. I'm sure I must have been near dehydration toward the end.

I remember going out once to check on Jim Martin and his TBX team working the Naval Gunfire Spotting Net. They were all fine but set up right out in plain sight on the beach. A Naval officer was with him--spotting the fire from the destroyers not too far off shore.

So I guess 2/8 had done its job from a radio communication point of view. (We had provided the only communication to the command ship and to the supporting naval gunfire ships.) Oddly enough I have never read any accounts dealing with this subject, nor have I ever been asked for my account. Perhaps if these words make it into print somewhere, someone will challenge my recollections, and add to all our knowledge about what other radio communications may have been taking place.

The TBX's were contained in two waterproof cast aluminum cabinets or cases plus the generator and the antenna bag. They had rubber gaskets around the edges of the covers to each of the cabinets. These covers could be screwed down so that the rubber gaskets made contact with the edge of the cabinet. The generator had similar waterproof covers over the handle and cable holes. It was a much more reliable radio set than the TBY (a one man portable radio) which was intended for short range tactical use. The TBY was difficult to waterproof and I assume that most of them failed because of their submersion on the way to the beach. I have no knowledge or at least no memory of what happened to any other of the radio sets even in our own battalion. I know we had TBY's on both our Battalion and Regimental Tactical nets, but cannot recall if we were able to communicate with them. Hopefully some of my fellow communicators can fill in that blank.

Following the Tarawa operation, we were moved to Hawaii where the Division went for regrouping or whatever. I remember that our Communication Chief, Master Technical Sergeant Maurice Lynch (later killed on Saipan) came by and asked me if I would like a medal or a promotion for my part in the Tarawa operation. I quickly chose the latter option and very soon became a 19 year old Staff Sergeant with about 30 months total service. If you are mathematically inclined you can deduce that I enlisted five days before my seventeenth birthday.

Joe, that about sums up my recollections for those three memorable days on Tarawa. The three days were pretty much more of the same each day and it went very fast for me. I wasn't in a great deal of danger, so long as I could keep my head down in the bunker we had been fortunate enough to inherit. As I recall we only lost the one wireman and Backus plus the unknown fate of our Communication Officer. One last little thing. When we took down the antenna after the operation was over, we discovered a bullet hole right through the antenna. The antenna was not large in diameter and we had exposed only about three feet up through the top of the bunker. We took pictures of it and I may still have it somewhere. (I do) Let me know if you have any questions, Joe.

Semper Fidelis Elwin (Al) Hart

Col USMC Ret"The wireman who was killed sitting on the side of our bunker was an 18 year old we called "Rabbit" from Texas. He was a particular favorite of Sergeant Dick Hogue, the Wire Chief and a close friend of mine. Dick knelt down over Rabbit's still body and cried like a baby, and kept saying no, no, no!

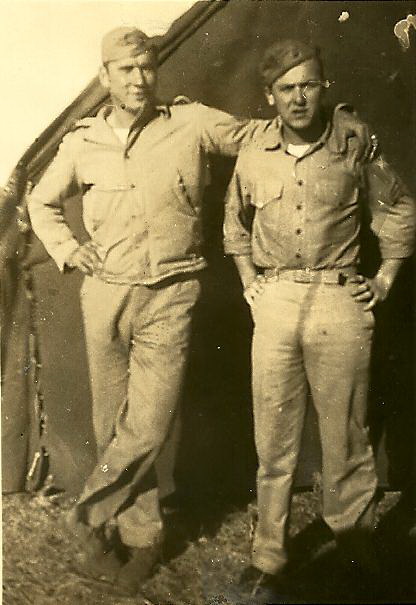

Me & Dick Hogue

We knew the round that killed Rabbit had come from a sniper in nearby palm trees, and several of our guys started peppering those trees with round after round from their carbines. We think their shots silenced the sniper since no more rounds were fired from the palm trees.

I got a nice response to my letter to Colonel Joe Alexander and a copy of his book entitled "UTMOST SAVAGERY - The Three Days of Tarawa" published by the Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland in 1995. Excerpts from that historic and accurate account of the battle of Tarawa are shown below. I received permission from Joe and the Naval Institute Press to include these excerpts from Joe's book.

From Page 118: "The sailor gunned the LCVP full-bore toward Red Three, hitting the reef so hard the impact knocked staff and commander into a heap. Crowe jumped up and vaulted over the gunwale into the water. Hatch, striving to protect his fragile film containers from the water, straggled behind. Crowe covered the five-hundred-yard wade so fast he reached dry ground only four minutes after the last LVT. Equally important, the LT 2/8 comm section arrived literally on Crowe's heels. It would take Sgt. Elwin "Al" Hart several frantic minutes to locate and assemble the major components of his TBX radio set--one of his men was down--but soon he would become the most valuable radio operator on the beach."

From Pages 125-126: "Good tactical communications, a rarity throughout the island, facilitated Crowe's relative success. Both his TBX sets were working, one linking Shore Fire Control Party #82 with the destroyers in the lagoon, the other in contact by lucky accident with the division command post on the Maryland. Eighteen year old Sergeant Hart manned the telegraph key and earphones on this rig. Hart could not raise Shoup (still making his way ashore) on the regimental command net, but he discovered that the persistent "unknown station" on that frequency was actually the division headquarters trying to contact anyone on the beach. Later, when Shoup established his command post (CP) ashore, Hart and LT 2/8 continued to serve as a relay station between the regimental commander and General Smith. Time and again throughout the battle, Sergeant Hart's Morse code signals would represent the "Voice of Tarawa" to the division commander and staff."

On a personal note, "Hatch" mentioned in the Page 118 extract above, was one Staff Sergeant Norman Hatch, a combat photographer, attached to our infantry battalion during the Tarawa operation. Norm and I were not acquainted during our time in the Tarawa operation, but we did become friends later in our lives. Information about that will be covered in a later chapter. Norm became rather famous for his photography of the Marine Corps combat operations in World War II, especially during the Tarawa and Iwo Jima combat operations. He recently was featured in a book entitled "War Shots", which is available through Amazon.

SSgt Hatch Photographing Attack on Sand Bunker on Tarawa - 3rd Day (See arrow)

Staff Sergeant Norman Hatch in New Zealand Prior to TarawaOne more bit of information which I failed to mention in my letter to Joe: we had two Navajo code talkers in our battalion. These guys were supposed to provide for secure voice transmissions over our radio circuits. Our experience with them was not all that successful. Their names were Tsosie and Baldwin (first names escape me) and they were both good Marines but had limited English language skills. Of course this limited their ability to provide information which they had received from their companion code talker on the other end of the radio circuit. I realize there was a lot of favorable publicity on the use of the Navajo code talkers during the Pacific campaigns, but my own evaluation was much less favorable.

In the photos shown hereafter, Eddie Fisher and I are holding the antenna which had received a bullet hole sometime during the operation. The flag which Walt Sears and I are holding was made of pure silk, and had an account of every battle the Japanese regiment that possessed it had fought in.

Eddie Fisher & Me Walt Sears & Me

MSgt Lynch & Elwin Hart (Lynch Later KIA on Saipan)

Japanese Concrete Bunkhouse Command Post

This chapter reprinted with permission from the author. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited

Send an Email:

copyright 2012 T.O.T.W.

Created 21 December 2012