| MICHAEL A. “MIKE”

MASTERS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [Mr.

Masters has given special permission to use portions of Once

A Marine Always A Marine (1988), his wartime

memoirs, to serve as the basis of this report for the Living Tarawa Veterans

Roster. His gesture is most

appreciated.] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| My

hometown was Chicago, and my parents’ house was really close to the Municipal

Airport. I graduated from high school

in June 1939. With a strong interest

in the U.S. Marine Corps and a similar interest in aviation, I enlisted in

the U.S. Marine Corps on 24 July 1939, a time when the Corps was an elite

military organization of about 18,000 active-duty men. Entry requirements were stringent, higher

than the other services, and all of that appealed immensely to me, to do my

best and be with the best in the service of our country. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

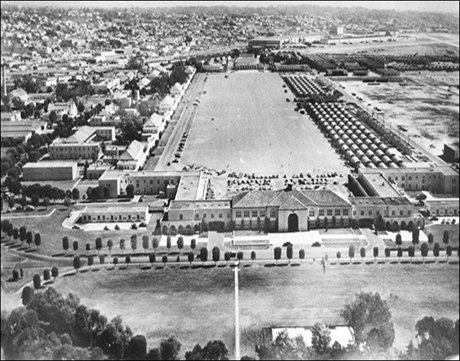

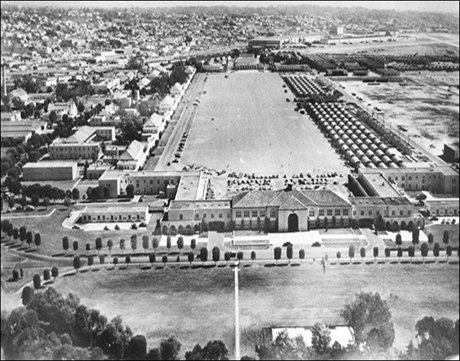

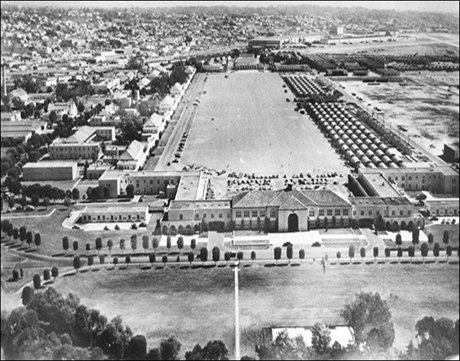

| With

$6.10 in my pocket for meals, I was sent by train to the Marine Corps Recruit

Depot in San Diego for boot camp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marine

Corps Recruiting Depot in San Diego, as Mike knew it |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.grunt.com/corps/uploads/stories/quonsethuts.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Training

was as tough as any Marine boot will tell you. “Boots,” as recruits were called, went

through strict and demanding training and indoctrination procedures: the GI haircut; receiving a bucket of

toilet articles (including a bag of Bull Durham tobacco and paper since we

were not allowed brand cigarettes); summer khaki uniforms and blue cover-all

fatigues (the kind farmers wore); olive-green dress uniforms, with Marine emblems;

two pairs of ankle-high shoes that laced up; tropical pith helmet; World War

I steel helmet and army pack; and finally, a ‘03 Springfield bolt-action

rifle still covered with cosmoline grease. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| US

Model 1903 Springfield rifle, caliber .30-06 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.nps.gov/spar/historyculture/the-1903-springfield-rifle.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| We

were taught that our rifle was always our own personal responsibility

wherever we went. “You are a Marine

first! That rifle is now a part of you

and is the only friend you

have. Your life may depend upon it

some day!” For mistreatment or

improper use of our rifle, penalties were severe. Simply by accidentally calling our rifle a

gun could cause swift and very humiliating repercussions when drill

instructors corrected such inappropriate use of the language in front of

fellow boots. Witnessing a drill

instructor’s tirade on a poor boot was a lesson we definitely remembered! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

August 1939, I graduated from boot camp in the 24th Platoon, and that opened doors to a number of specialized

career opportunities. I chose the

prestigious three-week Sea School and, ultimately, was assigned to the

battleship USS Tennessee (BB-43). Some of my

Sea School graduates were assigned to the USS Arizona which was sunk some two years later when the Japanese

attacked Pearl Harbor, and I will never forget those men. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Some of

the others from my recruit class were sent to defense battalions on Wake,

Midway and Guam where they made history defending those islands against

Japanese landings. Those who survived

on Wake and Guam and were sent as prisoners to Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

left the Tennessee in

mid-November 1941 and was on liberty at home in Chicago when my mother told

me she had heard a radio report that some Imperial Japanese Navy vessels had

left the Inland Sea for unspecified destinations. Something very ominous seemed to be

underway by the Japanese! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Tennessee (BB-43) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mike

Master’s ‘home’ between mid-October 1939 and mid-November 1941 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy: permission to use above photo from Bill

McWilliams (USAF, Colonel, Ret), |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| author

of SUNDAY IN HELL: Pearl Harbor Minute by Minute (2011); |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.west-point.org/class/usma1955/D/M/PHP.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Little

did anybody know or even predict at that time that within three weeks some

Japanese aircraft carriers would launch aircraft onto unsuspecting US Navy

ships at Pearl Harbor. That attack,

which severely but partially crippled operational capabilities of the US

Pacific fleet stationed there and resulted in the deaths of nearly 2,400

people, was what triggered America’s declaration of war against Imperial

Japan. My former ‘home at sea,’ the Tennessee, was damaged but

returned to duty almost eight months later and valiantly earned 10 battle

stars before the war ended. I have had

many occasions to contemplate what I missed by being transferred from the Tennessee so shortly before the

attack on Pearl Harbor. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| My

liberty in Chicago was finished very shortly before the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor, and I returned to the West Coast for several weeks to Yerba

Buena Island (where the San Francisco Bay Bridge is anchored on its route

between San Francisco and Oakland, California) to wait for my next

assignment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

February 1942, orders came and I left Yerba Buena to go to the Marine base in

San Diego. Expecting to be transported

to the docks to waiting transports, we instead headed east across the Bay

Bridge to Oakland, to an old secluded railway station which had obviously not

been used in years. With secrecy and

urgency, we boarded a troop train whose cars looked as if they hadn’t been

used since World War I. They had none

of the comforts anybody would associate with passenger coaches. They were converted steel boxcars with

several square windows and a plain square door on each side. Each car had a mixture of hard seats and

benches, with a head at each end. Not

surprisingly, these cars were called “cattle cars.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

San Diego, I was eventually assigned to a platoon of assault engineers in

Company D, 2nd

Battalion, 18th Marine Regiment (Pioneers), attached to the 2nd Marine

Division. [Mike’s 2nd Battalion was the 2nd Combat Engineer

Battalion whose mission was to “enhance the mobility, counter mobility, and

survivability of the Marine Division through combat and limited engineering

support.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.2ndmardiv.marines.mil/Units/2ndCombatEngineerBN.aspx |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_Combat_Engineer_Battalion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| By

June 1942, I was on my way to the Solomon Islands on the USS President Hayes (APA-20) where, beginning on 7 August, I

was part of America’s first ground offensive of World War II. The next day I

was in the landings on Tulagi Island, very close to Florida Island. Actually, our landing was at a village

named Sesapi which later became the Patrol Boat (PT) base from which our

future president John F. Kennedy operated for a while. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/p/PT-109.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

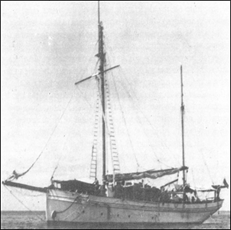

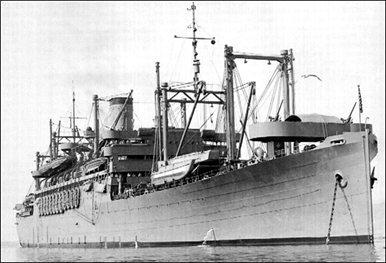

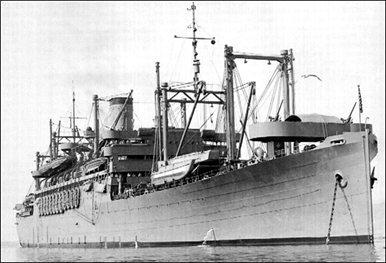

| USS President Hayes (APA-39), during

Guadalcanal landings 7-9 August 1942 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-p/ap39.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/guadlcnl/guad-1.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Notable

“firsts” in that operation included the first bayonet charge by Marines on

the causeway linking Gavutu and Tanambogo Islands (across Sealark Channel

from Guadalcanal) and the first American offensive use of artillery in World

War II. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As

Mike says, “To this day, the Japanese call the island of Guadalcanal “The

Island of Death,” where Marines and attached units inflicted more than 27,000

casualties, at a cost of more than 8,000 Marines and soldiers. Of this amount, 2,484 Marines were killed

or were missing. The slim victories of

the Marines were due to their discipline, training, and ability to withstand

hunger, fatigue, and disease” -- qualities that made all the difference in

subsequent Marine victories across the Pacific. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

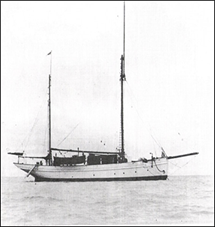

late January 1943, I boarded the USS President Adams (APA-19) bound for New Zealand. There, because of the combat at

Guadalcanal, Marine units were rebuilt to fighting strength, equipment was

replaced and some new equipment was handed out, and we routinely went through

extensive training prior to our next combat assignment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS President Adams (APA-19) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ships/APA/APA-19_PresidentAdams.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

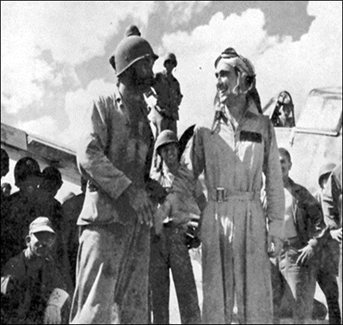

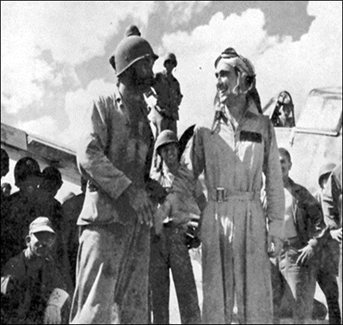

| Mike

Masters |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1943 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After a

nine-month stay in New Zealand (which Mike fondly refers to as his “Home Away

from Home”), the next engagement for Mike and the 2nd Marine Division was Operation

Galvanic at Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert

Islands. That topic becomes the

primary focus of this report on Mike Masters. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T A R

A W A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seventy-Two

Hours of Hell |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It was

late October 1943 and I was 21 years old.

The Battle of Guadalcanal was already in my rear view mirror, and I

had grown up fast. Our memorable stay in New Zealand was fast drawing to a

close. With new replacements, new M1

semi-automatic rifles, flamethrowers, training, training, and more training,

the men of our company were in top physical condition, ready and equipped to

take on the Japs. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

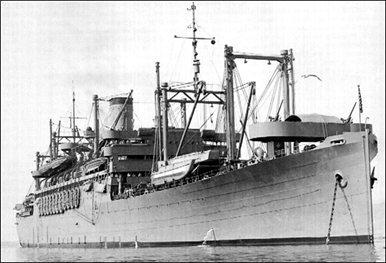

| Troops

and equipment were now thoroughly molded into an invincible fighting

force. The time had come; our

transports were waiting in Wellington Harbor to take us on “practice”

landings. Our platoon was again

detached, and we joined our battalion aboard the troop transport, USS Sheridan (APA-51). We were in Task Force 53.1.2 commanded by

Captain J.B. McGovern, USN. Besides

our own transport, this group of vessels included the Monrovia, Doyen, Virgo, La Salle and the Ashland. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://usssheridanapa51.com/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://pacific.valka.cz/forces/tf53.htm#galvan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Sheridan (APA-51) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.usssheridanapa51.com/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

was the NCO of a squad-sized shore party reconnaissance team that was part of

Company D, 2nd Battalion (Pioneers), 18th Marines. We were

assigned to land with the assault waves.

Word was purposely released that the transports were proceeding north

along the coast to Hawkes Bay for landing exercises and that our heavy

equipment would then be transported by rail back to the camps. This ruse may have fooled Tokyo Rose, but

it didn’t fool this “old salt” from Chicago. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

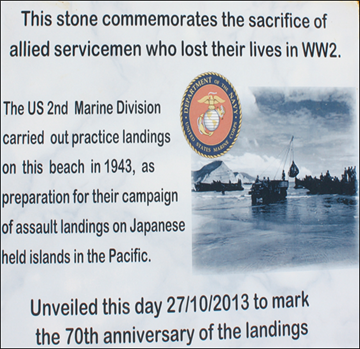

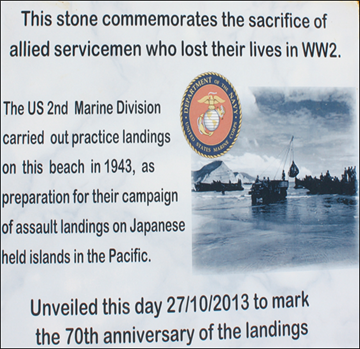

fact, practice landings did occur up on the north end of Hawkes Bay, at a

place called Mahia Bay. Just a few days prior to the 70th anniversary of the 2nd Marine Division’s practice landings in November 1943, members

of the New Zealand Military Vehicle Collectors Club (Robin Beale, current

president) held an event to commemorate our Marines’ original practice

landings. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

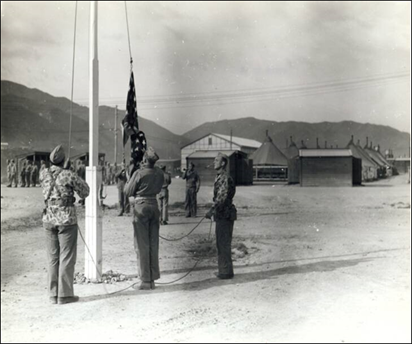

| The

four photographs below relate to the ceremony held on 27 October 2013 -

almost 70 years after our first stop there.

Three Marines from Camp Pendleton were flown out to New Zealand for

the ceremony. These Marines and one of

the US Embassy staff (wearing the red lapel poppy) were the guests of our

friends in New Zealand. At the far

right of this photo is an American flag draped over a rock cairn, covering a

plaque installed there by the people of New Zealand. At the appropriate moment during the

ceremony, our flag was lifted from the cairn and the new memorial plaque was

present for everybody to see. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| New

Zealanders and guests from the US Marines and the American Embassy meet on

Mahia Bay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| to

again thank our New Zealand hosts 70+ years ago prior to the unveiling of a

plaque commemorating our original practice landings there in early November

1943. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy: Robin Beale and Kevin Simmonds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| New

Zealand’s memorial plaque commemorating our Marines |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy:

Robin Beale and Kevin Simmonds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

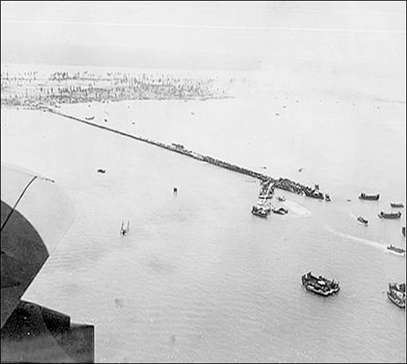

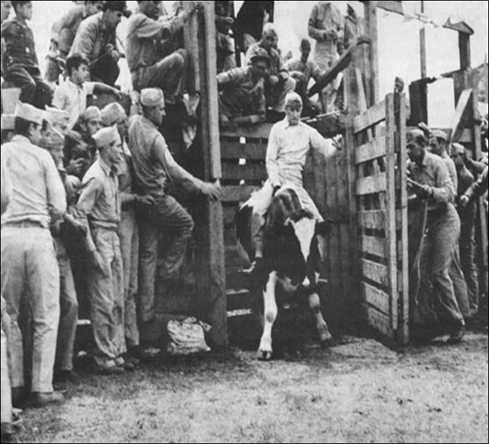

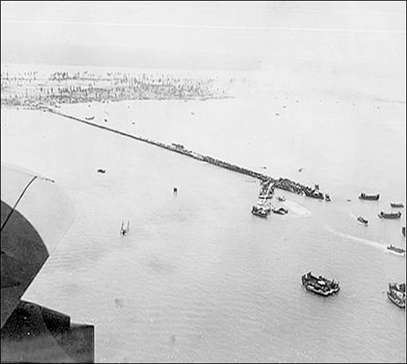

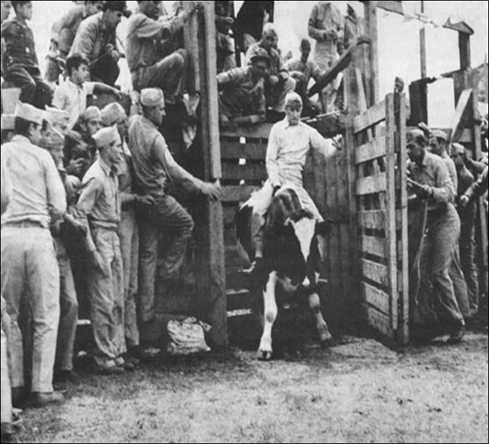

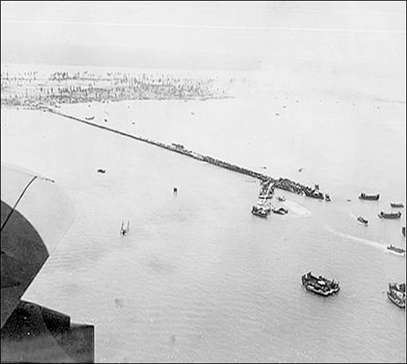

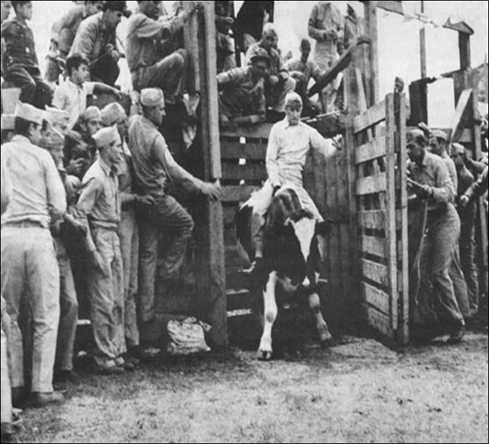

| 70-year

old photo of our Marines’ mock landings at Mahia Bay, November 1943 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy: Robin Beale |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/mock-landing-at-mahia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://nzmvcc.org.nz/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| If

only our Marines had had the beauty and tranquility of the Hawkes Bay area

when they finally reached their still unannounced destination later in

November 1943! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mahia

Bay on Hawkes Bay, North Island, New Zealand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Courtesy:

Robin Beale and Kevin Simmonds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Amphibious

maneuvers at Hawkes Bay maneuvers went off smoothly. The New Zealand Air Force assisted with

simulated air cover while the waters churned with boats hitting the beach all

day. That evening, all boats and even

the heavy equipment were ordered back to their transports for

re-embarking. Just as we left San

Diego a year prior, ships got underway, formed a staggered convoy flanked by

escort destroyers, and headed in a northerly direction, not south back to

Wellington. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

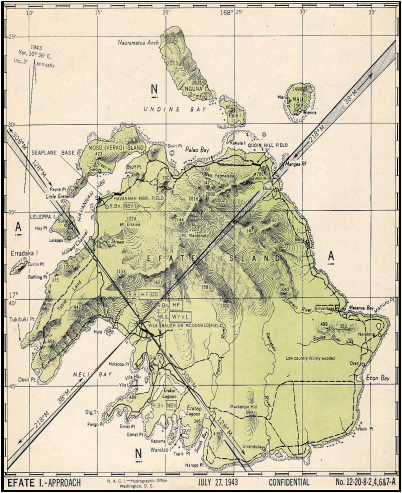

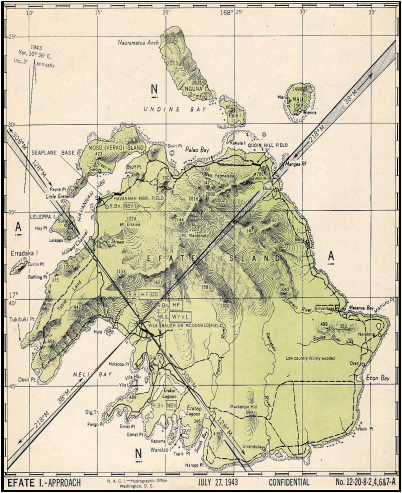

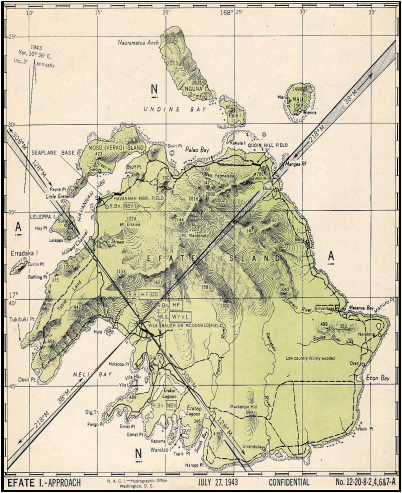

| After

several hours of sailing, the chilling word came over the ship’s

speakers: “To all Marines: We are not returning to our camps. This convoy is now proceeding into

combat. Our destination and plans will

be announced in a few days.” Several

days later our convoy arrived off Efate in the New Hebrides for another day

of landing exercises with other units of the fleet. That evening the transports anchored within

the harbor while Marine and Naval commanders held a final meeting. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After

Mike Masters' report was finished, supplementary information indicated where

he and his unit were for the few days at Efate Island. Sheridan went into Havannah Harbor up on Efate's northwest coast. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “SHERIDAN

arrived in Noumea, New Caledonia on 18 October 1943, debarked her troops, and

commenced unloading her cargo. She

sailed to Lamberton Harbor, Wellington, New Zealand on 21st, and on 1 November, sailed for Havannah Harbor, Efate Island,

New Hebrides in company with the battleship USS MARYLAND, and attack

transport USS MONROVIA.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| History of USS Sheridan (APA 51). Division of Naval History, Ships’

Histories Section,

Navy Department, 1952. http://usssheridanapa51.com/Sheridan_History.pdf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A WWII

US Navy Seabee map of Efate Island, New Hebrides |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NOTE: Havannah Harbor on northwest coast; Mele

Bay on southwest coast |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_approach_to_Efate_Island.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Our

stop basically served at least three purposes: waiting for more vessels to join our

convoy; practicing more amphibious landings at Mele Bay while waiting for

those additional vessels; and refueling Sheridan and resupplying the troops on board. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Good

planning and logistics made Havannah Harbor a good and practical place to be

at this time for our convoy. For at

least 18 months prior to our arrival at Havannah Harbor, the US Army and,

eventually, US Navy Seabees had been constructing port and airfield

facilities at Havannah Harbor.

Initiated by the 101st Engineer Regiment of the US Army's Americal Division and completed by

US Navy Seabees, this work gave the US Navy a support base that increasingly

enabled its warfare strategy in the South and Western Pacific. The first tough test of this build up was

the Navy's costly but ultimately successful performance in the nearby Battle

of the Coral Sea in May 1942. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Building_Bases/bases-24.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://americal.org/about.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cronin,

Francis. Under The Southern Cross: The Saga of the

Americal Division. Boston: Americal Division Veterans

Association, 1978. 15-16, 31-32. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Early

morning view to the west at Havannah Harbor, Efate Island |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| www.treesandfishes.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Only

a few of the high echelon commanders knew what the next target would be. Scuttlebutt was that it might be Wake

Island. We were excited to think that

we may be chosen to avenge our valiant counterparts--those Marines who held

off Japanese forces for sixteen days while dealing them a severe blow. The Battle of Wake Island began the same

day as Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, on 7 December 1941, and lasted

until Marines were overwhelmed and forced to surrender on 23 December

1941. American POWs from the defense

of Wake Island faced extreme maltreatment, including starvation, denial of

medical treatment, whippings and beheadings. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.historynet.com/wake-island-prisoners-of-world-war-ii.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mele

Bay, Efate, New Hebrides (now, Republic of Vanuatu) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.vanuatubeachbar.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/air-view-of-Mele-Bay.png |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A few

days out of Efate and still heading north by east, officers in charge got

word over the PA horn to release all confidential information on the upcoming

campaign and what was expected of the units. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

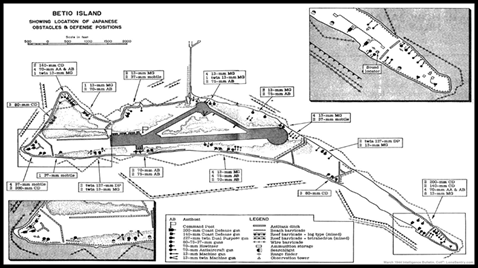

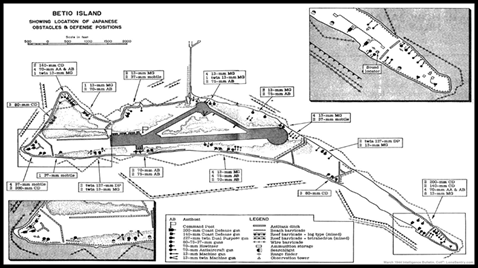

| We

still thought it may be Wake, until we gathered around a relief map of a

single horseshoe-shaped island and were informed that the assault would be on

a heavily defended, small island called Betio in the Tarawa Atoll, roughly

2,400 miles southwest of the Hawaiian Islands. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

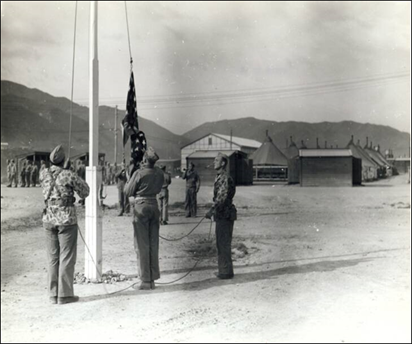

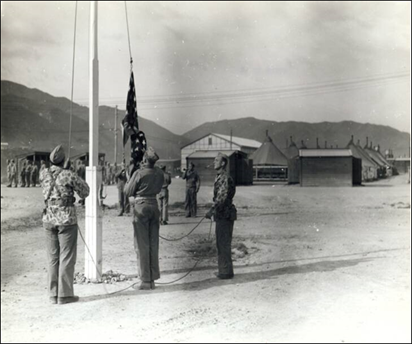

| On his

journey from Efate to Tarawa, Mike would have seen views like this. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NOTE: the 48-star “Old Glory” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://navyvets.tripod.com/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderpictures/wwiiconvoy.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

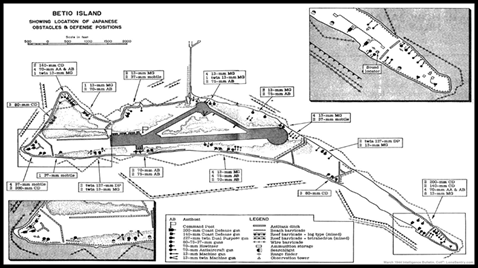

| Our

intelligence estimated that the Japanese had more than 5,000 well-trained

Naval Landing Force (Imperial Marines) personnel defending Betio. The island was just a little over two miles

long and a half-mile wide, but the Japs had sufficient time to build it into

a formidable fortress bristling with machine guns, 8” dual-purpose guns,

coast artillery, and tanks, all interlaced with tank traps and open trenches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Betio: Japanese obstacles and defense positions

thought to exist prior to attack |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.lonesentry.com/articles/jp-betio-island/tarawa-betio-island.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| While

en route, one of the transports limped back from the convoy, then a destroyer

dropped back to escort it. The next

day, we heard a rumor that the transport’s steering mechanism had jammed and

it could go only in wide circles, forcing it to reduce speed until the

problem was corrected. Next morning

the two ships caught up with the convoy.

Sailing a zigzag course within a convoy to evade preying Jap

submarines was still a hazard; any ship falling out had to take its chances

with an escort. I can imagine how

those Marines felt aboard that transport. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Most

of us took shipboard life in our strides, being veterans of the Guadalcanal

campaign. New replacements, fresh from

the States and going into combat for the first time, were apprehensive. The new men were fortunate to have this

time for indoctrination. The old salts

told them what to expect. A favorite

assurance heard was “Just stick with me, Mac!” Shipboard activities consisted of morning

calisthenics, tactical map sessions conducted by officers and NCOs, and

checking and re-checking equipment and weapons. Afternoons were generally free, because of

rising tropical temperatures. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| When

we were en route to Guadalcanal, our convoy was concealed by rainsqualls

right up to the morning of the landing.

Although this convoy was much larger -- spread over hundreds of miles

-- and the weather was clear right up to reaching the target, we still

weren’t detected by Japanese patrols.

A day before the landing one of our patrol planes spotted a lone

Japanese “Betty” bomber on radar just southwest of the convoy. The surprised intruder was shot down before

he could possibly reveal any information. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [20

November: D-Day]

Our huge armada approached Tarawa … Out of curiosity, I had to see

what was going on topside. It was

still dark. Troop transports were now

in their final approaches to their debarking areas, northwest of the channel

into Betio’s lagoon. Then it

happened: Dead ahead and off on the

horizon a Japanese red flare rocketed into the sky reportedly coming from

Betio. Our movements were finally

discovered. Our battleships

immediately opened fire with their main batteries, which lighted the horizon

with bright alternating flashes, followed by flashes and dull thumps as

shells landed on the island. I could

actually see the huge white-hot shells arching in the night right up to their

targets. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not

all the flashes were our exploding shells.

We were surprised to learn the Japanese had quickly reacted with their

heavy dual-purpose guns that were still operative and were returning our

ships’ fire--but not for long. The

Japanese had more than a year to prepare the defenses of Betio. An early aerial photo reconnaissance of the

island revealed Japanese still working on possible defenses on the northern

beaches, our landing sites. Mines were

in position but were never armed; interspersed were cement dihedral-angled

obstructions to deter boat landings.

Barbed wire interlaced the beach approaches forming fire lanes

designed to funnel incoming troops into 13-mm and 7.7-mm machine gun

positions. These were connected by a

series of interlacing zig-zag infantry trenches. Interior defenses were not as

concentrated. (A Japanese admiral

claimed that the island was impregnable and that it would take one hundred

years to be occupied.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After

our typical early breakfast of “styke-n-eygs” (steak-n-eggs), a practice

acquired while in New Zealand, Marines reported below decks to put on their

packs and make last-minute adjustments to their equipment. Then the well-known announcement came: “Now hear this! All Marines proceed to your debarking

stations!” Our working day started

early. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marines

proceeded through passageways and up ladders lighted only by red battle

lights, then stepped out on deck. The

sky was clear. A faint light began to

appear on clouds forming on the eastern horizon. For anyone who cared, it was going to be a

clear, hot day. This was also the

beginning of a day that a few fortunate Marines would remember for the rest

of their lives, with combat that added to the annals of Marine Corps history. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

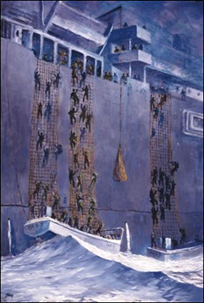

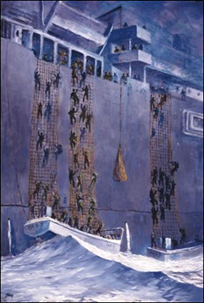

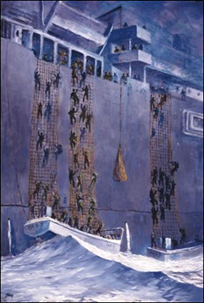

| After

a final roll call, my squad proceeded over the side. With rifles slung and helmet straps loose,

Marines headed down nets, holding on to vertical ropes to keep their fingers

from getting stepped on. “Heads up!”

came the order, as heavier equipment was lowered by ropes. This was the second combat landing for many

of us, but I still had a gut feeling that death was waiting just hours away. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pre-attack

embarkation into LCVPs amid ocean swells |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://cdn06.usni.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/story-large/stories/FF39AC4327A74BCB8C7A4E7E3B947A29.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Our

third wave was to embark in landing boats, as we lacked sufficient amphibious

tractors (called “amtracs”) to carry all the waves in. This would be the first time amtracs were

used in a direct assault landing. Our

boat milled around the USS Sheridan, circling until all boats joined up. Suddenly, several huge geysers erupted as

shells exploded between us and the transport.

A large dual-purpose Jap gun had again come to life from the northwest

point of the island, trying to disrupt our landing operations. Then another round came closer to our

ship. The next round surely would have

the range. The ship’s propeller came

to life, churning as it steamed out of range.

Our escort destroyers spotted the troublesome gun and immediately

opened fire. WHAM! WHAM! and the Jap gun was silent. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Colorized

photograph taken just before H-Hour as amtracs approach Betio’s north

shore |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ww2gyrene.org/assets/tarawa_goingin.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

morning sun was up but hardly visible:

dark billowing clouds of smoke covered the entire island. It had been less than half an hour since

our transports received return fire from the Japanese defenders. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Two

minesweepers slowly proceeded into the channel entrance to the lagoon to

clear our path of mines. Again, two

Japanese shore batteries, just beyond the extended pier, took the transports

under fire. Again, the leading

destroyer instantly engaged and silenced those positions. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Dashiell (DD-659) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.navsource.org/archives/05/0565915.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Ringgold (DD-500), first destroyer into the lagoon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/slugging-it-out-in-tarawa-lagoon/#comments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A

second destroyer (Ringgold)

entered the lagoon to assist in close fire support. It, too, was fired upon by Jap shore

batteries. Several shells splashed

close to the second destroyer. Within

minutes a shell punched into the mid-section of its starboard side, but

miraculously did not explode--no doubt a dud.

In revenge, the damaged destroyer trained its turrets on the suspected

position and opened fire. The huge

explosion signaled an obvious hit on the gun and its ammunition dump. (The

hyperlink below the Ringgold photograph is well-worth accessing: copy or type the URL into

a browser.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Now

assault crafts headed into the channel preceded by the picket boats which

would guide us to the line of departure, a few thousand yards from the beach,

and give us additional covering fire.

Naval shelling was still conducted at this point, although the island

was no longer visible--just clouds of red dust with patches of black smoke

rising from within. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

first two waves aligned with the picket boats and headed in; then our wave

formed up and followed. My landing

boat had been overhauled in New Zealand, with ¼” steel plates mounted on the

sides for added protection. The

additional weight made the boat draw more water, but it was still a visible

target. About two thousand yards out

we began to receive long-range automatic fire. Bullets sounding like hailstones bounced

off the plated sides while others whistled overhead. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Just

before we reached the edge of the coral reef, I looked through one of the

ramp openings to see how the first two waves on Red Beach 2 and 3 had

fared. The Japs waited until the

amtracs unloaded their men onto the beach, then opened fires with everything

they had. I watched Marines

desperately running to the sea wall at the water’s edge, while white tracer

bullets hailed on them from all angles.

I could see Marines falling while others still moved forward. It would be a miracle if any survived that

fusillade of bullets. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Saturation

bombing of Betio with more than 400,000 tons of explosives prior to and on

D-Day morning neutralized a majority of the dual-purpose anti-aircraft

positions and numerous anti-boat guns but was unsuccessful in eliminating

dug-in beach defenses that took our landing forces under violent, threatening

fire. Several amtracs found openings

in the sea wall and proceeded with their troops directly inland to the

northwest taxiways of the airstrip.

Others did not fare as well and were stopped on the beaches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Reaching

the reef’s edge, our boat’s coxswain for some reason decided to turn the boat

around, perhaps figuring the water might not be deep enough to clear the

coral reef. A Marine lieutenant in the

boat mistook the move, pulled his .45 pistol, and ordered, “Turn this boat

around coxswain, and head back in!” As

we turned about, we came alongside a boat that had been hit just before it

reached the reef. Survivors were

swimming to the nearest boats; several were hauled into our boat, shaken up

but not seriously wounded. One Marine,

his clothes in shreds and himself in shock, swam around the stern of our boat

to avoid incoming fire, decided there were too many in the boat already,

dropped back into the water, and swam farther out to another boat. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After

picking up survivors, we continued our approach to Red Beach 3, where I saw

the first two waves of men being mowed down.

Our ships’ fire let up as our fighter planes and dive bombers worked

the island over, passing directly over our heads, firing their machine guns,

and releasing their bomb loads as they nosed in at tree-top level. How unbelievable to see that tremendous

amount of firepower our Navy was unleashing on the Japs. And yet, as we

Marines would say, “Ya, there’s always one Jap bastard that didn’t get the

word and he’s waiting for you.” In

short, we never believed that shelling alone would eliminate the enemy. There was always a job left for the

Marines--to go in and finish them off. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

Japs did come to life with long-range machine gun fire, anti-boat guns,

mortars, and small-arms fire. The

withering firepower took its toll on other landing forces, especially those

who were dropped off at the edge of the shallow coral reef and had to wade

in. Several aerial bursts cut loose

over our boat, but were more powder than shrapnel. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Someone

again had given us the “bum dope” regarding tides around the island; there

was only three feet or less of water over the reef--not enough to carry boats

up to the beaches. Our coxswain again

headed for the reef’s edge, but the engine sputtered and stopped. He tried to start it, to no avail. To this day, I thank that young coxswain at

the helm for having enough sense to see that we weren’t going to make it over

that reef. Even under threat of a .45, he probably pulled a wire or

something. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As

the coxswain worked on the engine, the boat began to drift with the

current. Fortunately, the tide was

heading out and the boat drifted away from the island, back toward the

channel, still under a constant barrage from anti-boat guns or artillery

fire. One of the picket boats took us

under tow back to our transport, the Sheridan. After we climbed

aboard by way of the landing nets, the ship’s crew gave us orange juice and

coffee, and then we were ordered over the side again into another boat. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| That

was the longest morning of my life, yet it had been only an hour since our

boat had stalled. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [In the

following photograph, a production line at Higgins Industries Incorporated,

New Orleans, Louisiana.] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For

more on the Higgins landing craft legend, copy these URLs into a browser. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.higginsmemorial.com and

http://higginsclassicboats.org/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| By

now, someone had been convinced that boats were not making it over the reef,

and Marines walking in knee-deep water were easy prey for the Japs. Due to poor communications or because they

were ordered to, many boats still attempted to pass over the reef, only to go

aground or dump their passengers into the depths of the reef’s outer edges. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Our

second boat’s coxswain was now informed about the reef’s danger. We met an amtrac near the white coral reef

and transferred to the tracked vehicle for the short ride to the beach. Marine amtrac drivers alerted to the heavy

fire on Red Beach 3 decided to take us in along the west side of the 500-yard

wooden pier, affording some protection from the withering fire. Our landing

actually occurred on Red 2. Our amtrac

driver took us halfway down the length of the pier, keeping the amtrac close

to the pilings. “This is it,” he

yelled. “I’ve got to head back and

pick up another load.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sounds

of battle concentrated in such a limited area as Tarawa were deafening. The air was filled with the continuous

whistling and zinging of bullets, the close proximity of major-caliber

explosions, and the agony of hearing fellow Marines being killed all around

me. It’s strange how one’s mind works

under stress. I was alert and

determined, yet damned scared. I had a

right to be. For a second a strange

thought came to mind: Wouldn’t it be

nice to be somewhere else right now? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| There

was no way to dodge anything. All I

could do was hunch down and keep moving.

Once my ears adapted to the noise, my sixth sense and training took

over and I systematically ordered my scouting team forward toward the

beach. The carnage of floating bodies,

Marines as well as Japs, plus thousands of dead fish covered the shoreline,

while other bodies floated out to sea with the tides, some becoming victims

of sharks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| There

were still Jap snipers hidden under the pier, who took pot shots as Marines

went by. Just as I passed an opening

between the pilings, I heard a “zing,” and something hot brushed the seat of

my pants. Feeling the edge of my back

pocket, I discovered that a Jap sniper bullet had skimmed my left buttock,

cutting the threads from the seam of my lower left pocket! Assuming that it may have been a stray

bullet coming through the opening, but not taking any chances, I lobbed a

couple of grenades on both sides of the gap and continued toward the beach. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A

shock brought reality home. I passed a

dead Marine lying on a pile of coral along the pier, his pack blasted open

and his personal gear strewn on the coral rocks. Photographs of his family and a young lady

floated around him. I was sorry

afterward that I had viewed the incident.

Japanese carried similar pictures, several of which I had retained … In both cases, I thought, neither family

will ever know how the end came about. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Trained

first as a pioneer company, we were in Company D, 2nd Battalion, 18th Marines. We were

deployed as basically assault infantry:

We were experts in demolitions; we operated heavy equipment such as

bulldozers, we distilled drinking water; we handled flamethrowers. The Navy decided to call us Shore

Party. As a reconnaissance NCO, I was

assigned with my team of three men to go in with the assault troops and

reconnoiter the beach in my landing sector for places to bring in our

battalion supplies. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “March

Macabre,” a sketch by combat artist Kerr Eby, reflects the familiar Betio

scene of wounded or lifeless Marines being pulled to shelter under fire by

their buddies. U.S.

Navy Combat Art Collection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003120-00/sec6.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On

Tarawa (as we called the battle, referring to Betio) there was really no rear

echelon; once you hit the beach, if you were lucky you were in the front

lines, which were measured in yards along the sea wall. Fighting was at close quarters. In a sense it was organized confusion. Assault teams had overlapped upon landing

and were pinned down behind the three-foot-high coconut-log sea wall, just

yards from Japanese gun ports and infantry trenches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|