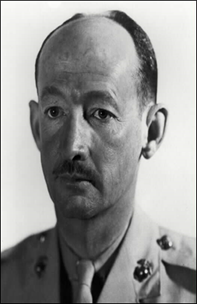

| HENRY C. NORMAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Some of

the best lessons I learned in life came from when we attacked the Japanese at

Tarawa, Saipan and Tinian. That is

when I learned my most valuable lesson:

that life is so precious. Every

day can have something very special to look forward to, and something good

can come from every day. It pays to

keep a positive outlook and be ready for whatever life throws your way. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| At

age 19, I voluntarily enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. The date was 11 December 1942. I came from Harrison, Michigan, about 150

miles northwest of Detroit. My 20th birthday was in New Zealand.

Fourteen weeks later, as a 60mm mortar man in Company G, 2nd Battalion, Eighth

Marines, we were at Tarawa in the fourth wave wading in to Red Beach 3, not

too far to the east of the long Government Pier. Looking back now from the vantage point of

my 90 years, I still remember things happening quite fast. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On 1

November 1943, we left New Zealand on the USS Heywood (APA-6), and I have since learned a lot about her storied

career during World War II. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Heywood (APA-6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Heywood_%28APA-6%29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heywood was originally built in 1919 for the Baltimore Mail Line and

named SS Steadfast. Acquired by the Navy on 26 October 1940,

she underwent extensive conversion, becoming the first in the Heywood-class of attack

transports. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

August 1942, Heywood

participated in the South Pacific campaign (Operation Watchtower) in the Solomon

Islands, at Tulagi and Guadalcanal, by bringing infantry and supplies to the

battle and evacuating the wounded and prisoners to Australia. In November and December 1942, she was back at Guadalcanal. In

early May 1943 in the North Pacific, she was active in the amphibious

landings in the Aleutian Islands of Attu (Operation Landgrab) and Kiska (Operation Cottage) before

returning to San Francisco with wounded veterans. Then with fresh infantry and supplies she

returned to the Aleutians to debark those men for occupation duty on Kiska,

arriving there on 15 August 1943. By early October 1943, she was back in the South Pacific, in

New Zealand, in amphibious assault training exercises preparing for our next

campaign. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I was

on board Heywood when we

left Wellington on 1 November 1943, and, ominously, we learned when we

boarded that she was fitted out to serve as a hospital ship during and after

our next campaign. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heywood landed infantry at Tarawa on 20 November and returned to

Pearl Harbor on 3 December for more amphibious assault training. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

late January 1944, Heywood

was in the Marshall Islands bringing men and supplies to the amphibious

landings on Kwajalein, Majuro and Eniwetok.

In mid-June and mid-July respectively, she landed troops at Saipan and

Tinian. On 20 October, she was in the

east, central Philippines landing troops at Leyte Gulf on 20 October. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| S.S. City of Baltimore in the livery of

the Baltimore Mail Line, pre-World War II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.gjenvick.com/HistoricalBrochures/BaltimoreMailLine/1930s-Brochure-NewShips-OneClass-LowCost.html#sthash.HqFjBv39.B1to7yAh.dpbs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On 9

January 1945, Heywood landed

troops at Lingayen Gulf on the west side of Luzon in the Philippines. A month later, she landed reinforcements on

Mindoro in the west, central Philippines, and, after overhaul Stateside on

the West Coast, she returned to the Western Pacific to land reinforcements at

Okinawa in the spring of 1945. She was in the Philippines when Japan declared

its surrender on 15 August (six days after our atomic attack on Nagasaki);

was in Tokyo Bay on 2 September when the formal surrender of all Imperial

Japanese forces was accepted on board the USS Missouri; and brought occupation troops into Tokyo Bay on 8 September

1945. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.navsource.org/archives/10/03/03006.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All

told, by the end of the war, Heywood had earned seven battle stars. She returned Stateside in early 1946 when

she was put into the Reserve Fleet until 1957 when she was scrapped. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/lines/baltimore.shtml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

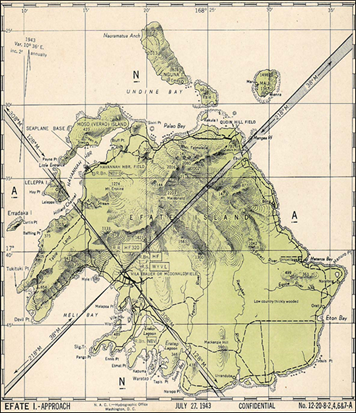

| About a

week out of Wellington, we arrived off the southwest coast of Efate Island in

the New Hebrides, a large island group in the South Pacific some 650 nautical

miles west northwest due Fiji. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

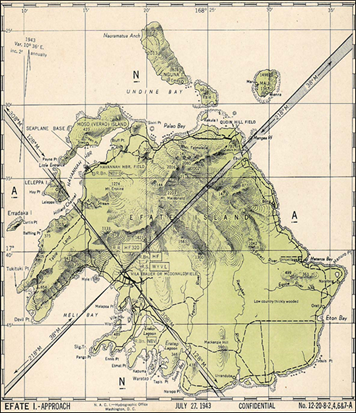

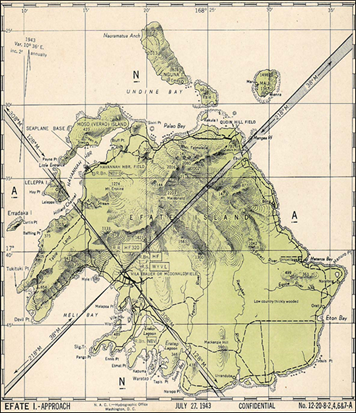

| A WWII

US Navy Seabee map of Efate, New Hebrides |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_approach_to_Efate_Island.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| We

were in Task Unit 53.1.1 of Transport Division Four of Task Group 53.1

Transport Group … all part of Task Force 53!

For almost a week, we had to wait for some other vessels to arrive and

join our convoy. We used our time

productively for the duration of the wait by practicing more amphibious

landings. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Some of

these landings took place in the Havannah Harbor area on the northwest coast

where construction of a naval support base was begun by personnel of the 101st Engineer Regiment of

the US Army’s Americal Division, some 19 months before we arrived. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Building_Bases/bases-24.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ACTC/actc-18.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cronin,

Francis. Under The Southern Cross: The Saga of the

Americal Division. Boston: Americal Division Veterans

Association, 1978. 15-16, 31-32. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Havannah

Harbor, Efate Island, New Hebrides (now, Republic of Vanuatu) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| www.treesandfishes.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Other

practice landings took place at Mele Bay on Efate’s southwest coast. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mele

Bay, Efate Island, New Hebrides (now, Republic of Vanuatu) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.vanuatubeachbar.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/air-view-of-Mele-Bay.png |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For us

Marines, Efate was heaven compared to the hell we would soon face. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Years

later, with historical hindsight, I was to learn that shortly before we left

Efate, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet and

Pacific Ocean Areas, had Operation Galvanic (that’s us Marines!) us in mind when he said, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Our

time has come to attack!" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.usmcmuseum.org/Exhibits_UncommonValor_p10.asp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq36-4.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| We left

Efate on 13 November 1943. Inexorably,

our convoy continued the long trek from New Zealand on a north, northeast

heading toward our still unannounced destination. Out on the open ocean, our convoy could be

seen for miles ahead in all directions. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A

representative photograph of a US Navy convoy in WW II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://navyvets.tripod.com/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderpictures/wwiiconvoy.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This

convoy was an impressive sight! The

men of the 2nd

Marine Division (Reinforced), consisting of three infantry regiments (2nd, 6th and 8th) were carried in at

least eleven transports. We were

reinforced by an artillery regiment (10th); a combat support regiment (18th), with engineers, pioneers and Seabees; at least two tank

companies; a medical battalion; and an amphibious tractor battalion. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Also,

ready to protect our convoy en route to our destination and ready to provide

fire support from offshore positions during the ensuing battles was an

impressive array of vessels: three

battleships, two heavy cruisers; three light cruisers; three aircraft

carriers; and nine destroyers. As well, we were joined by more vessels

carrying portions of the US Army’s 27th Infantry Division. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_tarawa.html#USassault |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A few

days out of Efate, all Marines were notified that Tarawa and Abemama Atolls

in the Gilbert Islands were to be our destination. The Marines’ primary target was Tarawa,

described as a strategic and recently reinforced stronghold for the

Japanese. Importantly, Betio Island at

Tarawa Atoll (the site of the main battle) had an airfield of strategic

importance. Our southern flank was to

be secured by our defeat of the small Japanese garrison on Abemama Atoll,

about 80 nautical miles southeast of Tarawa.

Our northern flank was to be secured by the 27th Infantry Division’s defeat of the small Japanese garrison on

Makin Atoll, about 105 nautical miles north Betio. The Japanese control of Tarawa Atoll and

nearby atolls was described as being a threat to the security of supply and

communications lines between the United States and her allies in New Zealand

and Australia. These were the reasons

given to explain and justify upcoming events. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| We were

also told that pre-attack naval and air bombardment of Betio - “the greatest concentration of aerial

bombardment and naval gunfire in the history of warfare” - would neutralize

any opposition we might encounter, but events proved that was an empty

promise with tragic and costly ramifications. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

fact, on 19 November 1943, Major General Julian C. Smith, Commander of the 2nd Marine Division, had

the following message read to all officers and men: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “A

great offensive to destroy the enemy in the central Pacific has begun. American air, sea, and land forces, of

which this division is a part, initiate this offensive by seizing

Japanese-held atolls in the Gilbert Islands, which will be used for future

operations. The task assigned to us is

to capture the atolls of Tarawa and Abemama. Army units of our Fifth

Amphibious Corps are simultaneously attacking Makin, 150 miles north of

Tarawa. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For the

past 3 days Army, Navy, and Marine Corps aircraft have been carrying out

bombardment attacks on our objectives.

They are neutralizing, and will continue to neutralize, other Japanese

air bases adjacent to the Gilbert Islands. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Early

this morning combatant ships of our Navy bombarded Tarawa. Our Navy screens our operations and will

support our attack tomorrow morning with the greatest concentration of aerial

bombardment and naval gunfire in the history of warfare. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It will

remain with us until our objective is secured and our defenses are

established. Garrison forces are

already enroute to relieve us as soon as we have completed our job of

clearing our objective of Japanese forces. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This

division was especially chosen by the high command for the assault on Tarawa

because of its battle experience and its combat efficiency. Their confidence will not be betrayed. We are the first American troops to attack

a defended atoll. What we do here will

set a standard for all future operations in the central Pacific area. Observers from other Marine divisions and

from other branches of our armed services, as well as those of our allies,

have been detailed to witness our operations.

Representatives of the press are present. Our people back home are eagerly awaiting

news of our victories. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I know

that you are well-trained and fit for the tasks assigned to you. You will quickly overrun the Japanese

forces; you will decisively defeat and destroy the treacherous enemies of our

country; your success will add new laurels to the glorious tradition of our

troops. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Good

luck and God bless you all.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-Tarawa/USMC-M-Tarawa-J.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.2dmardiv.com/Major_General_Julian_C_Smith.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In the

darkness of night on 19/20 November 1943, Task Force 53.1 arrives off the

west coast of Betio Island … the westerly-most and largest island in Tarawa

Atoll. The stage is set for what would

eventually be called “Bloody Tarawa” and one of the most significant Marine

Corps battles in history. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On

Saturday, 20 November 1943, we are awakened at about 0300. We check all our gear once more. In my case that means my M1 carbine and 10

- 12 clips of ammo, each clip containing about 12 rounds. You better believe

it: we know we have to conserve our ammo!

I also have with me one 60mm (2.36” diameter) mortar tube in my

pack. As well, I’ve got a gas mask; a

first aid pouch; and some grenades. We’ve had a good breakfast of steak and

eggs, and I remember a doctor saying that all that food might not be the best

for us in terms of trying to digest it while in combat. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heywood finds its anchorage at Transport Area Baker (a few miles out to sea,

southwest of Temakin Point on Betio Island). With some of my squad, we’ve

gone out went on deck to watch the Navy shell Betio. It didn’t take long, though, for Heywood to be repositioned to

Transport Area Able (a few miles further out to sea and northwest off the

northwest point of Betio, often called the “Bird’s Beak” because of its

contours). In darkness, debarkation began as Marines begin crawling down

cargo nets strung down the sides of Heywood and board amtracs (amphibious tractors) and LCVPs (landing

craft, vehicle, personnel). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

remember going over the rail and scrambling down cargo nets to a LCVP

(Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel; also commonly called a Higgins boat)

rising and falling on the ocean swells.

Not easy doing that in the dark way back then, and only a little less

difficult in daylight. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Based

on calculations aided by the U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications

Department, the next photograph was obviously taken after I had boarded the

LCVP. The photograph was taken in the

early daylight hours after sunrise (0611) on D-Day, 20 November 1943. This calculation is based on the presence

of full daylight, the clear images in the distance and the number of smaller

craft appearing in foreground and distance. Heywood is seen on the left, middle distance offloading amtracs shortly before they

and their precious cargo - our Marines - depart for their run to Red Beach 3

on Betio’s northern shore. By the time

this photograph was taken, I had already departed Heywood for the rendezvous

area used prior to our departure for Red 3. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USS Heywood (middle distance, left)

lowers an amtrac on D-Day at Betio, 20 November 1943 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/npswapa/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003120-00/sec4a.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U.S.

NAVAL OBSERVATORY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ASTRONOMICAL

APPLICATIONS DEPARTMENT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sun

Data for Saturday, 20 November 1943

Universal Time + 12h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Betio,

Tarawa Atoll [1.26° N, 172.53° E] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Begin

civil twilight

05:49 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sunrise

6:11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sun

transit

12:13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sunset

18:16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| End

civil twilight

18:38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneDay.php |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I was

one of about 30 guys in our boat.

Milling around waiting nearly three hours to rendezvous with other

boats was uncomfortable for a lot of guys; diesel exhaust and pitching and

rolling in the water does strange things to a guy’s sense of balance and the

stability of a guy’s stomach! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| To

this day, I remember talking on the way to our rendezvous point with Lt.

Kenneth Mosher, a fellow Michigander from Flint. Of all things, we reminisced

about pheasant hunting back home! I

don’t think I was too worried about what was going to happen; this was my

first experience going into combat.

However, I do think guys who had already been in amphibious landings

at Guadalcanal probably felt differently because they knew how bad things

could get. Maybe I should have been

more concerned, but I simply did not know what really could happen. I knew how to go through the mechanics of

amphibious landings; we had practiced that a lot. Reflecting back on that morning nearly some

70 years later, I must have been partly naïve and partly in denial. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In 1984,

my son and I had a chance to meet Lt. Mosher at an event in Minnesota. I was really looking forward to seeing him

again and catching up on a lot.

Unfortunately, he had a change in plans, and I never have seen him

since our time in the Corps. I was

told he lived for many years in Texas. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This

photo is a good example of what we looked like on our run in to Red 3 at

Betio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/ref/Gators/img/Gators-23.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

guess many of us thought the ride in to the beach and the landing would be

fairly uneventful, in view of the tremendous pre-attack punishment given to

Betio by our Navy ships. We were soon

caught by surprise, though, because it didn’t take too long to figure out

that most Japanese defenders had hunkered down underground to wait out the

Navy’s bombardment. When we arrived,

they really turned their guns on us.

That caused a lot of havoc, injuries and deaths. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In

the 4th wave into

Red Beach 3, we were in the first wave of the Higgins boats that day,

arriving a little after 0900.

Amphibious tractors, also known as amtracs, had gone ashore in earlier

waves. At about 500 yards out from the

beach, our boat got caught on the reef and we quickly got out amid enemy fire

coming from shore and waded in to the beach.

One particular challenge walking across that reef came as a complete

surprise: some of our own aircraft had dropped bombs for some reason on the

reef before we even got there. The

result was huge bomb craters had been blown into the reef, and, as they were

underwater, we couldn’t see them until we suddenly stumbled into them! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

ride in was like a bad dream. Time

seemed to stand still. It still seems

that way. We were being fired on as we struggled to shore. In chest-high water, we didn’t present much

of a target, but a number of guys took head shots and it was all over for

them even before they got to shore.

There was no place to hide, and lady luck was a companion for some of

us, but certainly not for all of us!

With oil and blood in the water, some guys would take a gulp of foul

air and dirty water and submerge themselves, trying to walk toward shore.

When your air ran out, you knew you had to rise up and try to catch another

gasp of air, knowing full well you might be picked off by shore fire that

reached out beyond the end of the pier.

Some of us slowly got over by the long Government Pier to our right,

and that’s where I remember coming ashore, perhaps 100 yards east of that

pier. We were part of a Weapons

Company, and Lt. Mosher was the CO of the platoon I was in. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Things

were very hectic. Our entire mortar

squad became scattered. Nobody could

say we were a coherent fighting unit.

We were more like individuals just fighting and trying to stay

alive. Most of us went over the palm

log seawall within the first 30 - 40 minutes. The seawall saved quite a few

Marines, but many of the defenders were in the slit trench just a few yards

beyond the wall, and there were a few pillboxes nearby. I think it was an engineer from the 18th Regiment who threw a

satchel charge over the seawall and hit a large ammo dump. Wow!

That explosion shook the whole island!

Another huge explosion occurred shortly after the first one. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Initially

on that first day in my area close to the land end of the Government Pier, we

used just small arms, bazookas and flamethrowers. As a mortar squad, we used our mortars very

little. The main reason for that

relates to the nature of the terrain: Betio was a sandy, flat and small area

for a battle to be waged. At about

291 acres, it was less than half the size of Central Park in New York City;

its highest point of land was only about 8 feet above sea level. If we used

our mortar at all, we fired them just about straight up. If we had fired at a low trajectory, our rounds

would have gone all the way across the island into the ocean on the other

side! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Our

squad had six men. Different guys

carried parts of our 60mm mortar, a weapon used for close-in support of

ground troops. I carried the 25-pound

mortar tube; another carried the 15-pound base plate; another carried the

bi-pod leg structure on which the tube was mounted; a gunner carried and

operated the sighting unit; a gunner (like I was) dropped the shells in the

tube; and all of us carried a few rounds of the unexpended mortar shells as

well as all our other gear. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “Here’s my squad’s

weapon. We were good with it.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/voices/2010/13/m224-60mm-mortar.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For

all of D-Day, I was in the area near the north turn-around area of the

airfield. At about 1100, near the

center of the airstrip, I was wounded by a sniper some distance away. He was obviously aiming for my head;

instead, he only got me in the back in my right shoulder area. Just a flesh wound, it was only 12 inches

away from the back of my head! Thank

God his aim was off! At about 1830,

after dark, I was wounded again, this time by some sporadic machine gun fire

from, I think, over on the nearby big concrete bunker. I still have a bluish scar under my jaw,

but I never really suffered from those rounds in later years. Lady luck was with me again! I spent the

rest of that night bandaged in the shoulder and neck areas lying as close to

the ground as I could in the slit trench near the palm log seawall. My one concern was surviving the night so

that I could be evacuated the next morning. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

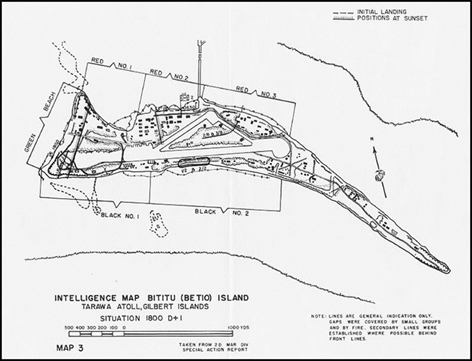

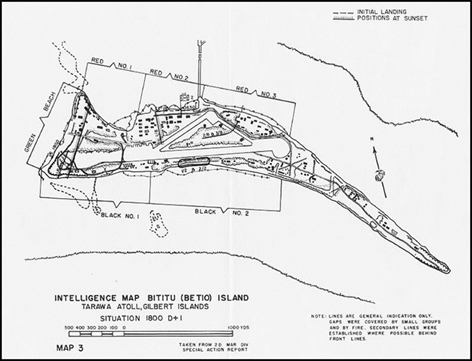

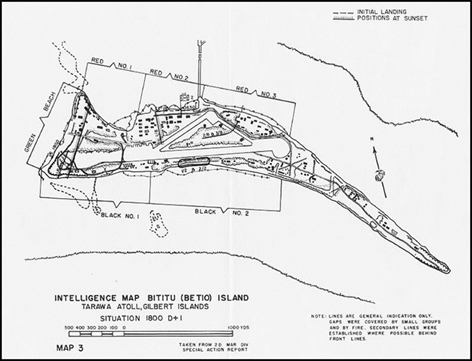

| “This

shows where I came ashore and was wounded on D+1” (SEE

TEXT) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:USMC-M-Tarawa-3.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Out

there in the tropics, the temperature really didn’t go down much at night

from the high temperatures of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit! We were very concerned the Japanese

defenders would stage some sort of counterattack, but in our area that did

not happen. I think that was because

some of our shelling had killed the Japanese commander, Admiral

Shibasaki. With him dead, nobody was

in the position to order a counterattack.

All I was concerned about was just hanging in there until

sunrise. It wasn’t nice. I didn’t

sleep all night. I thought I might not

even live through the night and might not even see the sun come up. I can tell you … strange things and strange

sounds happened during the night, making me feel really vulnerable. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

next day (D+1), I was evacuated. I was

really one of the walking wounded. One

guy helped in the dangerous process of supporting me and wading with me next

to the Government Pier out to its end where I was picked up by a Higgins boat

and taken to one of our transports. I

can’t remember its name now. I was

hoisted up the side of the transport because I could not climb up the cargo

nets. They patched me up, and for a few days I stayed on that transport

before we departed on the long journey to Honolulu. While we were still there

and on our way to Honolulu, I remember seeing and hearing several burials at

sea. The firing party would fire three

volley salutes, and then came the playing of “Taps.” It was very sad, but it was necessary. I guess the trip to Honolulu took about 10

days. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

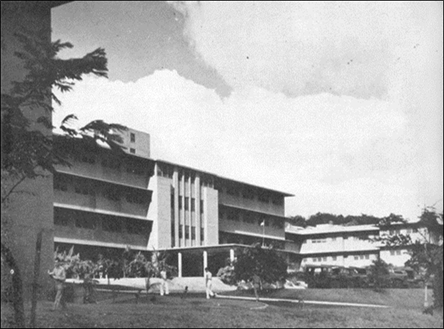

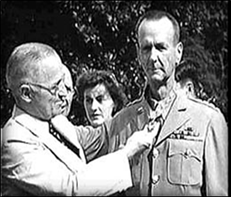

| In my

case, our arrival in Honolulu was on 7 December 1943, two-years to the day

after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

We came in right through the harbor entrance and up to the East Loch. I was out on deck because I was beginning

to feel better by this time. I could

see several ships still sticking up out of the water and some buildings were

still in wrecked condition from the Japanese attacks. We went to a dock where

we disembarked to be taken to the Aeia Naval Hospital. My stay there lasted perhaps a week, and I remember when a

group of about 17 of us were taken from the hospital to Waikiki Beach where

Admiral Nimitz came and pinned Purple Hearts on us. He seemed like a really decent,

straightforward kind of guy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aiea

Naval Hospital, Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://ww2db.com/images/other_none814.jpg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| From

Honolulu, I was taken by ship to Hilo on the east coast of the Big Island of

Hawaii, and from there by truck I was taken to Camp Tarawa to rejoin my

unit. My arrival there was sometime

between Christmas and New Year’s Day; I’m not sure now exactly what day it

was. At Camp Tarawa, we received a

lot of replacement Marines and trained really hard every day. We had marches of varying lengths, were

taken frequently for live firing drills, and practiced rubber boat landings

on nearby beaches and on beaches near Hilo.

There were softball and volleyball teams, with games often between us

enlisted guys and officers. I still

remember the time when the 2nd Marine Division rodeo was held; it went on for 2 or 3 days

and was a lot of fun. In my mind

then, I thought the area of the Parker Ranch where Camp Tarawa was located

looked a lot like what I thought Texas looked like. Oh, and the cold! After the heat at Tarawa, the cold here had

its own downside. It really stimulated

us, and we moved a lot faster just to keep warm. One day, there was a big explosion caused

by some guy who had what he thought was a dud of a shell that he had brought

back to his tent. Tragically, it was not

a dud and a couple of guys got killed.

We also did a lot of construction there with the Seabees, and we got

to eat with them. That was good

because their food was better than ours! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Looking

back now, over 70 years later, I have to say that the Battle of Tarawa was

very intense and hectic. They said we

needed to take Tarawa because of the strategic value of the airfield. It was

named after Lt. Hawkins, one of the first guys to land on Betio when us

Marines landed. In retrospect, taking

Tarawa was the first stepping stone for many of us in a series of battles

across the western Pacific. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| From

Camp Tarawa, we left for Honolulu.

Evidence of the attack on Pearl Harbor was everywhere, including near

the harbor entrance. Some of the

LSTs ahead of us in our convoy got caught up in some huge explosions over in

the West Loch of Pearl Harbor. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

wreck of LST480 in the Pearl Harbor West Loch explosions of May 1944 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/160480.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.cnic.navy.mil/HAWAII/AboutUs/History/WestLochDisaster/index.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| We

had not completed our rendezvous with the others ahead of us, but if we had,

we too would have been caught up in those explosions. Lady luck visited us again! We saw and heard these explosions, and we

saw smoky fires that burned for quite a while. To this day, one of the wrecked LSTs in

the explosion remains, as you see, where it was scuttled some 70 years ago …

stuck on the shore of Waipio Peninsula, not far from the entrance to Pearl

Harbor. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seven

months after Tarawa, we were in the initial landings of Operation Forager on Saipan. We had a very tough time there, where on 15

June 1944, D-Day, I was in the 2nd wave to the right of the beachhead on the southwest

shore. I think we were the last

company on Yellow Beach 3, and the Japs really tried to drive us off even

before we landed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| At

Tinian on 25 July 1944, on D-Day, our unit was part of the fake assault not

far from Tinian Town (presently known as San Jose Village). On D+1 at Tinian Town itself, we actually

landed, right behind the 4th Marine Division. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Here’s

something that will interest you: One day several years ago I saw the book Pacific Warriors, by Eric Hammel

(2006). On the cover of that book

(above) is a photo of Marines landing at Tinian, and was I ever surprised to

see that I am actually in that photograph! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "That’s

me, the guy behind the group of three in the left front area of this, as we

came ashore at Tinian!" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USMC

photo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.stamfordhistory.org/ww2_tinian.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

remember moving up the western side of Tinian for about a week and a

half. We even saw some of the suicide

jumps there, though not nearly as many as jumps as those whichoccurred from

the cliffs up on Marpi Point on the north end of Saipan. That was awful. As was done on Saipan, our Marines tried to

talk those people out of jumping, but we weren’t very successful in our

efforts. Two corroborative and

poignant statements on these suicide jumps on Saipan and Tinian may be found

at … |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/pacific-koyu-shiroma/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/tinian.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I

remember, too, that we built a camp up on the northern end of Tinian, near

the airfields built by the Japanese.

Only much later did I learn that it was from these airstrips that

B-29s later came in and made regular raids on Japan and that it was from

these airstrips that the atomic bombs were taken by B-29s to attack Hiroshima

and Nagasaki and bring the war to an end. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Thomas,

Gordon and Max Gordon-Witts. Ruin From The Air: The Atomic Mission to Hiroshima. London: Hamish

Hamilton, 1977. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It

was at our camp by the airstrips on Tinian that that I was called in one

Sunday to the 1st

Sergeant’s office. I had been wounded

on my left leg earlier on Tinian, shortly after going ashore. I was told that a new law had gone into

effect where, if a guy had been wounded twice in situations where, in each

incident, at least 48 hours of hospital rehab was required, that guy would be

ordered home. That was my situation, and so it was from Tinian that I was

ordered back Stateside. I remember

being on a transport (can’t remember which one) coming into San Francisco

Bay, under the Golden Gate Bridge, seeing large billboard signs for Lucky

Strike cigarettes and Coca Cola! It

was 31 October 1944 … Halloween! What

a treat! Wow! Did it ever feel good to be back home! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I took

the train down to San Diego to check in, get new uniforms and a health check,

and then I was given a 30-day “en route” pass to go home. I went to Chicago, then Detroit and then

back to Harrison, Michigan where I had enlisted in the Marine Corps back in

December 1942. I was home between 13 November and 15 December, and then new

orders came in that took me to a most unusual opportunity. Here's a hint! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| President

Franklin D. Roosevelt, age 65 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Photo

taken at the Yalta Conference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| about

two months before he died |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.firetown.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I was

ordered to Washington, DC, to the Marine Corps Headquarters on 8th and I Street, and

assigned to the Presidential Guard at the White House! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| My

living quarters were up in the Catoctin Mountains in Maryland at what is now

called Camp David. Back then, FDR

called the place “Shangri-la.” With

other Marines in the Presidential Guard, we lived in nice cabins and commuted

to Downtown DC. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Spring

had already arrived when FDR and his staff relocated to the Little White

House in the hills outside of Warm Springs, Georgia on 30 March 1945. The

entire entourage went to the train station in DC and then had about a 14-hour

ride to our destination. Consisting of

about 50 guys (including our own support staff and cooks), the Marine Guard

itself lived in six-man tents about 50 yards away from the Little White

House. We did our four-hour shifts of

guard duty from small guard shacks located discreetly in various places on

the grounds not far from FDR’s residence. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On

the train trip south, FDR really was not well at all. I did not actually see FDR, but various

people on his staff and several Navy doctors were around him all the time.

On Sunday, 15 April, FDR was supposed to come to our mess for

supper. We built a wooden ramp so he

could be wheeled up and into our mess, but at the last minute, his plans were

changed because as that week progressed, he was feeling progressively

worse. More Navy cars and Navy doctors

arrived. And then, on Thursday, 12 April,

while he was sitting for a portrait, he had a stroke and died about two hours

later. He was only 65. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| President

Franklin Roosevelt’s Little White House |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_White_House |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On

the day FDR died, I was on guard in one of those duty shacks. The ramp we had built to help him get into

our mess was used, instead, to assist his casket up to the railroad car that

transported his body back to Washington, DC.

I accompanied the hearse to the railway station, but I did not

accompany the funeral party back to Washington. A group of other Marines accompanied the

casket back to Washington, and I had to stay at the Little White House for a

few more days before taking a train back to Washington. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Up

until I was discharged on 13 October 1945, I lived in the barracks at the

Marine Corps Headquarters and was involved with a number of very different

activities. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For

example, on two occasions I remember, we escorted prominent returning

military people in homecoming parades in Washington. One parade was for Brigadier General James

P. S. Devereux, one of the Marine

commanders at Wake Island who, as a Major, led the stiff, 15-day defense but

ultimate surrender of the 1st Defense Battalion Marine defenders at Wake Island in December

1941. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Major James P.S.

Devereux

Brigadier General James P.S. Devereux |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CO, 1st Defense Battalion, Wake Island USMC

photo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seen here as a POW at Shanghai, c.

Jan 1942 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sources

of biographic information and both photos of General Devereux are, with

thanks: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.ibiblio.org |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/worldwari1/p/wakeisland.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://dundalkeagle.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/jpsdever.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| General

Devereux (1903-1988), Navy Cross recipient and Republican congressman,

represented Maryland from the 2nd Congressional District House of Representatives for four

terms from 1951-1959. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Another

homecoming parade was held for General Jonathan Wainwright who had led

American and Filipino forces against the attacking Japanese on Corregidor in

the Philippines in the spring of 1942.

After General MacArthur obeyed FDR and left Manila and headed for

Australia, Wainwright was given command of Corregidor, and he was the

American officer obliged to surrender all American and Filipino forces to the

Japanese on 6 May 1942. The infamous

Bataan Death March was one result of that surrender. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| http://eyewitnesstohistory.com/bataandeathmarch.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wainwright,

by this time a Lieutenant General, had been the highest-ranking American POW

during the war (for 40 months), incarcerated and very badly treated by the

Japanese throughout the rest of the war until liberated by the Soviet Red

Army in August 1945. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| General

Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright (1946) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

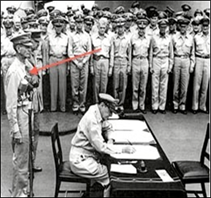

| Wainwright, on left behind MacArthur President Truman bestows

Medal of Honor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| WWII surrender ceremony, 2 Sep

1945 White House

Rose Garden, 10 Sep 1945 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sources

of biographic information and all photos of General Wainwright are, with

thanks, from Duane Colt Denfield, Ph.D. (18 November 2009) and

www.historylink.org at

http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=9212 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Live

news film footage of celebrations welcoming General Wainwright home follows: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| https://ia700602.us.archive.org/12/items/September101945Newsreel-NationWelcomesHeroOfCorregidor/45_09_10_Newsreel_Nation_Welcomes_Hero_Of_Corregidor_512kb.mp4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [Henry

continues …] I also participated in many funerals details at Arlington