HOW I REMEMBER MY ARRIVAL AT "HELEN"

I was in H & S Company, Second Regiment, Second Division FMF. My job was radio operator. It was November 20, 1943.

After seeing action at Guadalcanal, our outfit had spent nine months in New Zealand for rest and training. We left New Zealand knowing only that we were headed for the Central Pacific Area.

H & S Company was divided up and put aboard two transports. Our group went aboard the APA Zeilin. Life on ship was always the same: steaming holds and lack of drinking water. The scuttlebutt was we were going to retake Wake Island.

My buddy, John M. Gross -- who received the Navy Cross at Tarawa -- and I slept topside under a Higgins boat. This was to take advantage of cool, fresh night air. John was later killed in action on Saipan.

Our convoy pulled into Efate in the New Hebrides to pick up supplies and the big ships. After a short stay the convoy headed north. Still the scuttlebutt was we were going to be the avengers of Wake Island. It wasn't long before the straight dope came over the loud speakers. We were going to attack the heavily defended atoll of Tarawa, Island of Betio.

We were also informed Tojo had announced to the world "a hundred thousand United States Marines couldn't take Tarawa." We looked around and doubted if there were that many men in the whole convoy. The U. S. Navy informed the troops not to worry -- when they finished with Helen it would be nothing but a pile of sand in the Pacific.

As dawn of "D Day" approached, I think, to the man, each thought this landing was going to be a pushover. Some thought of their buddies on Bougainville, who were having a real rough time. Later I found out one of my friends there didn't make it.

This operation was different; the training had been something new. The holds of the ships were nearly empty - something we were not used to. Usually gear is piled high in every corner. Not this trip! This also gave way for more scuttlebutt. It meant one thing to us -- we wouldn't be there long. The thought also entered our minds that maybe, after the operation (which was going to be so easy) we would head for the States.

As dawn came the transports pulled into Tarawa Lagoon -- our first glimpse of an LST. Some thought maybe it was Japanese. The ships anchored and prepared to disembark troops and supplies. The Navy planes were making the last strafing runs on the landing beaches. The big ships were hurling their final shells. Helen was talking a real beating. We could see trees and fire. Maybe the island wasn't going to be as flattened as the Navy said.

Next, to everyone's surprise, the transports were being shelled from shore. As quickly as possible the transports moved out of range. So this was going to be an easy operation!

"H Hour" was changed, as it would take longer for the troops to reach their line of departure, being further from shore. A mad scramble was next, getting everything going into the Higgins boats. The first thing we noticed, the water was really rough. Many of the men, including myself, got seasick.

Our group was to head for the beach as soon as the amphibian tractors landed the troops of the first wave; that is, all the amphibs that were operating after the landing.

Soon it became apparent things were in a jumbled-up mess. The beachmasters were like madmen trying to organize the jumble of boats and tractors. John Gross was aboard another boat with his radio as radioman for Col. Shoup. History has told what a heroic job John and the Colonel did at Tarawa.

The water seemed to get rougher all the time. My radio was taking a real pounding on the deck of our Higgins boat. I had to then put it on my back to save it. This made it hard to operate. By this time I was really sick and many others were, too. The rough water kept a good spray of water coming over us so things were kept washed off. We were too crowded to do any moving around.

It was now apparent communications were very much lacking. We couldn't set up our radio equipment so it was decided to find any amphib running, pile the radios and operators in, and head for our spot on the beach. Most of the amphibs running were taking wounded put to the ships. Finally we found one and pulled along side. The officer in charge of our boat gave the operators new orders -- "get these radios ashore!"

I didn't care if I lived or died by this time, so I went along with three other radio men. As soon as we were aboard the tractor, the difference in motion caused my seasickness to leave. It was apparent all was not well here, either. The driver had taken in troops in the first wave and landed them successfully. As he was backing off the reef, they took a second hit in the side. It was bad enough so they were taking on water.

We instructed the driver to head for the beach near the pier. He said, "That's going to be hard, as all those dead Japs the Navy killed for us came back to life and the reef is jammed with dead and wounded Marines." He said, "Anyway, here we go. I'll try to put you where you want to go or as near as possible." We traveled approximately one hundred yards and the engine quit. No amount of coaxing would bring it to life. We started to drift toward the large end of the island. Our hailing and waving at boats and tractors for help was to no avail; all we received was a wave back. They had their troubles, too.

The engine was tried from time to time, but to no avail. Later in the afternoon the engine did come to life. We turned around and headed back toward the pier. After going approximately 50 yards, it quit. Looking shoreward we could see movement on the beach but couldn't tell if it was Marines or Japs. The decision was made to try to raise someone on one of the radios. We gave this up as there was no answer on any of our frequencies on either radio set.

All of a sudden a 37mm opened up on us from shore -- probably because of three sets of antennas aboard -- one from the tractor, two from our radios. The shells landed close on all sides of us, but none hit. We decided to lower the antennas in a hurry. After doing this, they stopped shelling. During this time the two amphib drivers worked madly on the engine; still it wounld't start.

Darkness was beginning to fall -- the battery was about gone. One more try and the engine caught and roared into action. Again we headed for the pier. By this time we had drifted almost past the large end of the island.

Slowly we headed toward the pier. All of a sudden, in the darkness, an LCVP loomed up. The officer in charge advised us to tie up as he was anchoring until somehow, someone would get some information on what was going on. All night long we tried to figure out what was happening on shore. Machine guns rattled -- both American and Japanese. Rifle and mortar fire was heavy. We really felt useless just waiting.

The radios just were not getting through, so we decided to pack them back up. There wasn't any dry spot aboard because of all the water the tractor had taken on. There wasn't any sleep to be had except dozing from time to time. Things quieted down ashore toward morning.

As dawn came the Navy planes started bombing and strafing the small end of the island. Then, to our amazement, planes of all types started bombarding the pier.1 This seemed very close to our troops ashore; in fact it really wasn't a great deal of distance from us. We also were wondering just where our troops were located. So this was going to be just a pile of sand in the Pacific! It was still an island with trees and many, many Japanese.

The bombing of the pier prompted the LCVP to start moving. We stayed moored to it and they headed for the new type ship, which was an LST. We were ordered to tie up and come aboard. To our amazement there was part of our H & S Company aboard waiting to go ashore. Now we really knew this operation was in trouble.

Then all of H & S Company, Second Marines, that hadn't reached shore were put aboard Higgins boats and we headed for the beach next to the pier. I do not remember anything in particular about our trip in, except we landed on the pier about thirty yards from shore. We were immediately waved off and finally reached shore under sniper fire.

The spot we had picked to land the amphibian tractor was a large pillbox that wasn't knocked out until the second day.

As we arrived at our appointed spot on the beach, which was behind a large bunker, there was my buddy, John Gross, with the only operating ship-to-shore radio. John and Col. Shoup had made it in along the pier under very heavy fire. John asked just where had I been! He was getting tired and wanted relief. I was assigned the radio while John found a foxhole for some rest.

This photo shows Shoup's command post. The Marine on the left

might be Gordon Stevens and to the right operating the radio with headphones is Bill Travis.

The bearded Marine operating the generator behind them is Frank "Henry"

Lupien. According to Bill Haddad this picture is probably from the third day. The TBX radio

Travis is operating did not arrive until the second day. Corpsman Ray

Duffee was on Red 2 during the second day and needed some Marines to help carry some wounded

back to the relative safety of the beach. He came to the CP and probably talked to my dad, Gordon

Stevens. Two guys, who were probably from the H&S communications company, accompanied Ray and

were wounded themselves.

Click here to view the entire picture

We who had just arrived ashore were amazed at the small beachhead the Marines were holding in this area. To our right was a bunker with Japs in that just couldn't be knocked out. The pillboxes and bunkers were so ingeniously constructed that flamethrowers and grenades were just not enough to knock them out.

On the second day a large bulldozer came ashore and one of its first missions was to roll this bunker into a pile of sand and logs.

One of the most outstanding things I remember about Tarawa was the water. About six weeks before the operation began, five-gallon water cans were filled with fresh water and stored until we needed them. Some of these cans were painted on the inside -- others were not. The water in the painted cans absorbed the paint taste or oil taste. Although the water itself was all right, it was unbearable to drink. With nothing else around, that was it! If one was lucky he might find a can that was not painted inside. The water in these cans tasted like water but the cans had rusted inside and were thick with rust -- but, it did taste like water!

Another wild night without sleep!! John and I kept the radio going. As time passed, a radio or telephone was put in running order or connected with fresh batteries. Most of this equipment was around but it wasn't healthy walking around looking for things and stay healthy. Slowly and painfully, needed gear was located and put to good use.

The next morning the men assigned the job of locating the bodies on the reef, started bringing them to mass graves. One was behind our bunker toward the runway.

Seeing this really started to bring the full impact of the battle before each man. Everyone had buddies missing but thought maybe things would slowly get organized or their buddies would show up. Part of our company landed on the large end of the island way off the assigned landing beach. But this time we were in radio comunication with them but didn't know just who was where.

The third day we moved across the island, making room for the replacemants that would be coming in.

Our communications company was now getting organized -- scattered pockets of H&S 2 all together once more as a unit. Now we were finding out who the dead and wounded were and how it happened.

The night of the third day was rather calm compared to the previous two nights. Estimates on how many Japs were still alive on the tail of Betio varied. We expected a Banzai charge down the airstrip; however it didn't materialize in our area.

The morning of the fourth day was spent in trying to clean up. Many were looking for souveniers, or just relaxing. There were still some pillboxes with live Japs giving the Marines trouble, but other units were assigned to that job.

|

|

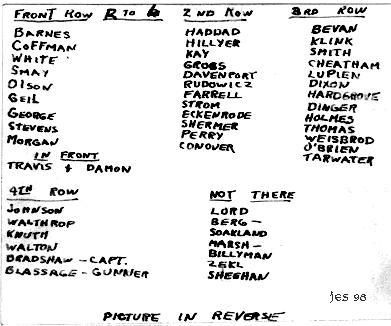

This picture shows most of the men from H&S Co. 2nd Marines after the battle, including my dad, Gordon Stevens, and his good buddy John Gross. It was taken just before they went back aboard ship. The second picture lists the names of the Marines. Those listed as "not there" were either wounded or killed.

Before we really thought about it, the word came down that the assault troops were leaving. All units assembled, even though some were very few in number. We headed for the pier and Higgins boats to be taken back out to the troop transports.

We were promised Thanksgiving dinner after we were aboard. I'll never forget the officer in charge of the loading and unloading of troops, who was an Ensign. For some reason he would not give permission for our particular group of boats to come alongside the cargo nets. We just circled and waited for orders. It was hours before we finally received word to come alongside. The water had been rough and all were soaked from the spray coming over the bow. I never did see that Ensign again all during the trip to Hawaii. The ship was the U.S.S. Biddle, used during World War I. It was the ship aboard which the other half of H&S Company came to the Gilberts.

It was as we expected -- the troops aboard before us received the turkey dinner. We each received two peach halves and something to drink! This was just another day of World War II.

The ship was very crowded. All officers' quarters were filled with the wounded. Many of the officers and men were sleeping topside.

The convoy was moving at a good pace, as many of the ships had wounded aboard. We headed toward the Hawaiian Islands. Our ship docked at Oahu Harbor, and we thought as soon as the wounded were off, clean clothes would be issued and we could have liberty. Our stay was three days -- but the only liberty was for the officers. The third night things were made ready to put to sea. It was a good thing, as the troops were becoming very restless.

The Marine band came down to the docks and played as we pulled out. One piece was "California, Here We Come." Our thoughts were that perhaps we were going stateside.

The next morning we lined the rails looking at the ocean. Now we knew it was stateside for us. On the starboard side of the ship the men saw something else -- the snow-covered peaks of the Island of Hawaii. That morning we docked at Hilo, Hawaii, and were sent to new training at Camp Tarawa.

I was a Private First Class at Tarawa and was discharged later as a Sargeant.

This was the operation called "Helen" as I saw it.

Gordon H. Stevens

H & S - 2

Fleet Marine Force, Pacific

"The Three Musketeers"

Bob Geil, Gordon Stevens, and John Gross in New Zealand 1943.

This picture was carried in my dad's wallet for the rest of his life.

Both Gross and Geil were killed on Saipan from friendly fire.

The brotherhood of battle.

Boot Camp 1942. One tough Gyrene.

The following excerpts are from a letter my dad sent to Eric Hammel in response to questions about the his Tarawa account:

On John Gross:

Gross, as near as I can remember, was the same age(age

23). He enlisted about a week before I did (January

19, 1942) and used to kid kid me about having a lower serial number.

John was from Racine, Wisconsin, and worked for an optical company in Milwaukee.

Staff Sargeant Pete Zurlinden, the Marine Combat Correspondent, sent the story of John's citation to both Racine papers and Milwaukee papers. Each town was having a feud on whose favorite son he was. John looked forward to going home and enjoying the publicity. I do not remember what officer wanted to give John the Medal of Honor, but a panel for the Second settled on the Navy Cross. I remember well how nervous John was the morning they awarded him the medal.

John was from a large family but I lost contact with them after his Mother and Father died. The family had John brought back to Racine and they buried him in the hometown cemetary. John was killed by our own rockets fired from a plane on Saipan, along with two other of my buddies. There were other casualties in another outfit, plus some minor wounds among our group. I had written home to John's folks saying he was killed by Jap shellfire but some Marine replacement in our outfit told his folks the truth and they became very bitter about John's death. I visited the folks a number of times amd wrote, but later stopped after his parents died. His brother, Jerome, was in the Army on Saipan and came to see me there.

John was also very serious over a redhead from New Zealand by the name of Alice. I never did hear how she took John's death as her address was in John's effects.

On H & S Company --

Captain John T. Bradshaw was our Communications Officer when we left the states

on July 1, 1942. At Tarawa the second in command of H & S Co. was Marine Gunner

Blassage. He was from Aurora, Illinois, and had been in the Marines in China

before World War II. Our communications platoon was formed at Camp Elliot

in San Diego. We were radio, telephone, and message center personnal for the

H & S Company. At Tarawa there were 49 forward echelon officers and men in

the Company.

I remember another incident. There was a large shell crater only a few yards away and to the right looking toward the pier, that we set up the larger radios in. It was also a place to rest when there was an opportunity, as it was really big. It was late in the day on D + 2 as I came off the radio by the bunker. We were starting to walk around upright and I was standing on the edge of the crater talking to someone down in, when Captain Bradshaw hollered for me to get down NOW!! At the same time a sniper took a couple of shots at me and I moved fast down inside. The Captain sure bawled me out for that!

Bradshaw really kept his men in good shape. We often were training when other men were not busy in New Zealand. It got so we knew the hills behind our camp at McKay's Crossing as well as our tent area. When we were not hiking, we were having communication problems with the radio and message center men. The radio operators often grumbled as we had to know telephone communications as well as radio. As far as I know, our radio men were the only ones in the whole regiment that had to know how to climb ploes and string wire. On days when the weather was bad, Bradshaw had us learning how to operate the message center equipment. Likewise, the telephone men and message center men had to know each other's operations. As I remember of Captain Bradshaw, he was -- I think -- from Boston.

On Col. Shoup --

I remember the night of D + 1. how he and Major Culhane, who was our R3 officer

for the second regiment, tried to use the available artillery to the best

advantge. As soon as one area was covered with shells, a message of one form

or another came through and Col. Shoup and Major Culhane would groan and try

to lay maps out under some canvas to plot either the mortar or 75mm pack howitzer

where they were needed the most. The artillery and mortars were located to

our right as we faced the pier.

There were many problems on Betio that Col. Shoup had, but the mess on the beaches could only be solved by communications and during D Day and D + 1 they were the Colonel's big problem. This was reflected by the messages and the constant questions -- where was so and so -- what outfit was where -- and who was in command. As this information slowly came through, the Colonel's outstanding leadership began to show. I think Major Culhane's leadership was outstanding, also.

As to the cans of water on Betio,

...once the foul-tasting water was down, it did not seem to matter. I do not

know of anyone getting sick, but that doesn't mean there wasn't anyone! I

think the conditions we fought under at Tarawa had something to do with the

water not bothering us. It was human nature, where nothing else is available,

to be satisfied with what is on hand. When the replacements who were relieving

us came ashore, the stink of the dead made them regurgitate, while we who

were there and could do nothing about it, were used to it. Some said the odor

could be smelled for miles out to sea.

About the bunker being bulldozed over,

...This was one of the first bunkers to be knocked out the first day, D Day

-- or so was thought. As supplies came in along the pier, the troops would

be pinned down by sniper fire. The men would be astonished to find the fire

coming from this small pillbox. I do not know how many times it was blasted,

but it was a relief when it was crushed and overrun. I remember John Gross

telling me there were live Japs in there but they couldn't get out. The pillbox

was overrun on D + 2.

Gordon H. Stevens

End Notes

1. This was an attempt to destory the machineguns in the Niminoa. The

bombing and strafing was called off after finding the accuracy of the

planes left much to be desired.

copyright 2002 T.O.T.W.

Created 11 January 2000 - Updated 4 January 2004

Return to Index