An interview with Les Groshong

by Nancy Brewer with additions by Les Groshong

#275101

Nancy conducted this interview as part of her research for her Master's thesis

during March and April 2000. Via email she presented a question to Les along

with a Kerr Eby drawing. Nancy's unique interview technique

along with Les's excellent writing ability make these exchanges quite fascinating

reading. Nancy's thesis has since been completed. For more information please

send an email. Don't forget to read the second article from Les. Thanks to

Nancy and Les for making this interview available to Tarawa

on the Web.

"Fear"

29 March 2000

Dear Nancy,

In one way I am glad to be helping you because I believe that I have something to contribute to an understanding of Marines in WW2, however at the same time, I realize that it takes so much more than just talk to understand men in combat. I know that to understand some things that you inquire about I will have to discuss things that you do not inquire about, so I'll probably do it my way and you can always ask questions, and none are out of bounds. OK?

First let's discuss fear. If a person is unafraid there is no fear. Most of the time in combat there is very little fear. If you are in a hole, nobody is shooting your way, and you are eating or day dreaming you are probably not afraid. If you are afraid, there are dozens of different kinds of fear you may experience. I am told that the Eskimos have hundreds of different words for snow and ice, and likewise, the Indians had hundreds of different words for deer. We have only the one word fear to describe dozens of different feelings that we call fear. I have said on occasion that I have experienced 27 different kinds of fear, and I would guess that that is an understatement. Think about your fears. Driving, flying, alone at night, sickness, parents health, school examinations, etc., and there is no end to the kinds of things that we fear.

Now to combat fear, and I only speak for myself, the worst fears that I experienced were not the ones that were most threatening to my life, but the ones in which I was either defenseless, as during a shelling or a bombing, or the fears to the unknown, like the day before combat. A few examples: On Guadalcanal, my buddy and I (We are still friends, and still communicate, and have gotten together six or seven times since the war) located our radio just below the top of a hill, and our antenna was above the hilltop. we dug in, and shortly thereafter we were obviously targeted by a long range artillery piece. Shells were hitting right above us, or missing the hilltop, landing several hundreds yards away. In a certain sense I felt secure, but I developed a laughing, shaking-let's say it, a hysterical reaction. My buddy reacted the same way. It was a singular experience for us. Now on other occasions, like the landing on Tarawa, when I had something to do, I could do it with very little debilitating behavior. Having something to do made it less frightening. Perhaps your experiences will confirm this belief. More later.

"Fear Again"

29 March 2000

Dear Nancy,

Final comments on fear. The worst fear that I ever had was the night prior to the Saipan landing, when I could taste the bile in my throat. The next morning on my way to the beach I was excited, and remember shouting at a rocket launching ship, "Give them hell!" The second worst fear was after I was wounded, and on my way out to safety. I had received my million dollar wound, the one that gets you home, and only had to survive a four mile boat ride to survive the war. For the first time I was making deals with God. In neither case was I in the greatest danger. So much for fear.

Up to this point I haven't mentioned Tarawa. Tarawa was not the roughest landing that I made. At Saipan we lost three quarters of our total casualties during the war, and most of them were lost in the first few days. I was on that island for about fifteen minutes, wounded, and on my way back to the ship. If I am not mistaken, we were the first wounded to leave the island. Tarawa was not my worst landing. From my point of view, any landing in which you are killed has to be considered the worst possible. Getting wounded comes in second.

There are various ways of measuring the difficulty of a battle, and the historian likes to look at the figures. The number dead, the number involved, the days duration, etc., and I have no problem with that, but I think that the individual can only make his own judgment, based on his experiences, and I also have no problem with that. You can find Marines defending their battle experiences as the roughest, fiercest , etc., and I find no trouble with that. Frankly, I don't find it very important to anyone except those involved. Bragging rights don't do much for history or the dead. I am no expert on Tarawa history, but I have never heard anything about how great the planning was. Everything that I have read says that we knew too little about the tides, although we did the best to find out. We were denied needed Amtrak's by some admiral, and most importantly, we were short of needed information on defenses, effectiveness of our shelling, communication problems brought about by naval shelling, and last minute changes in the Air Force bombing missions. From my point of view, these are typical of all landings. It is a rare operation that doesn't have these problems. In the hospital in Hawaii after Saipan, I talked to our Battalion Commander, who was also wounded, and he said that if he had to do it over again he would practice doing everything wrong, in order to be prepared for the foul-ups that inevitably occur. We had landed on the wrong beach. Enough for now.

"The Moment"

29 March 2000

Dear Nancy,I have been trying to understand the question about my defining moment. I really don't know what that is. The closest that I can come to an answer, I guess, is when I realized that I could do the work that had to be done. I did not know that at any given moment, but when required or needed I could do what had to be done.

I'll give you a Tarawa answer. When we landed on Guadalcanal I got in the bow of the boat, and was one of the first to land. It so happens that the landing was unopposed. Being wiser by the time of the Tarawa landing I decided to ride in the middle of the boat. When boarding a landing craft you unload your gear in case you have to swim, and then you set down. I did that. Upon approaching the end of the pier I put on my gear, and stood up. The ramp had dropped six inches and stuck. Here is the hard part of the story. Hard because it is impossible to have happened, but I could see no one in front of me. I moved forward, and started hitting the ramp with my foot. I had mixed feelings about it dropping, but I continued until it dropped. I now realize that the rest of the men probably hadn't stood up. And that was why I felt alone. Anyway, that is the kind of experience that I had often enough to know that I could do the job. You are the first person to ever hear that story. As for the Marines under the pier, there were openings every 20 to 30 feet. I didn't stop or take notice of the men under the pier until they started backing away from me. At that time I'd say that there were maybe 10 or 12 men there with me. The number going in to the beach was just a small trickle, maybe one man every 30 or 40 feet. After reaching shore my outfit was never organized. Four of us were carrying parts of a radio, and I never saw any of them on the beach.

"Two Radios...." 6 November 2000

Dear Jon,

I note that one feature of the story was omitted for me it was an essential part of my experience.

Here it is:"We were in reserve, but quickly ordered to land. By 11:30 am we were landed on the end of the pier. It was smoldering, and I used the antenna case, that I was carrying, to set on. It soon caught fire, and so did my pant's leg. I abandoned my antenna case, and put my leg in the water to douse the fire. One radio lost. I climbed up onto the pier, and saw another radio (TBY), which I carried along side of the pier halfway to the shore, when an officer asked me to call offshore for more ammunitions, for more troops, and for the removal of the wounded. Try as I might there was no response. While doing this, someone spotted two Japanese soldiers hidden in the structure of the pier. I only became aware of this when everyone around me started to look over my head, and back away from my position. Mentally, I could see a rifle pointed to the back of my head, so I dove in the water. About six feet into the dive my head was suddenly jerked backward, then the radio followed me into the water. Two radios lost."

30 March 2000

Dear Nancy,Thank you for the kind words. When I look back on the wise things that I have done, invariably they have been the times that I have kept my mouth shut. (I am not kidding ) In looking over your questions I seem to have covered most of them, however I do have a few additional comments to make.

You asked about Marines under the pier. Upon reflection I now remember that the water at the end of the pier was five feet deep. The radio that I picked up had to be carried on my shoulder. The man that left it there was probably 4 or 5 inches shorter than I am, and so there is no question of his judgment in leaving it behind. I found out about who left it behind when Neil Buckley, now living in Studio City, told me in 1990, that he had left it on the pier. As I moved toward the shore the water got more shallow, and I now believe that there was no ground space to set on prior to my stopping point. To me,that means that there was not an accumulation of reluctant Marines under the pier.

One thing that troubles me a little is the very few Marines that I actually saw moving toward the shore. After my landing boat experience I am beginning to believe that my vision and mind were completely on what I was doing, and not on what was going on. Very possible. This detail is to fine tune your mind on some of the important facts concerning the pier....

"Down The Net"

31 March 2000

Dear Nancy,

In a $75 dollar book called "The Marines" pg. 189, there is an Eby print in black and white of "Down the Net." I have looked at it before, and to me it looked well done. For me, the very first thing I looked for was to see if the artist was aware of the importance of not putting your hands on the cross ropes, but only on the perpendicular ropes, to avoid being stepped on. Then I looked for details of the equipment carried. These were line soldiers. Many men have to carry heavy weapons, mortars, machine guns, radios, etc. Radiomen carried their radios on their chests coming down that ladder, which meant leaning out about 15 inches from ladder. I worried every time that I had to do that. As for the talent of the artist, there are few less qualified to make that judgment than I. Before your inquiry, I had looked, and to some extent studied the drawing, and approved. I don't think that the artist would want much more than that.

Here is an actual photo of coming down the net for comparison. - Editor

"Rope Ladder"

31 March 2000

Dear Nancy,

Although I don't remember anyone ever being seriously injured going down a rope ladder, I have always thought of it as one of the most dangerous, and most frightening non-combat exercises that we had to endure. The distance down was usually around thirty feet, the ship was usually rocking and rolling, and the landing craft was often bobbing and weaving. You start off loaded down with a back pack, canteens and bayonets attached to your waist, a rifle over your back, and maybe a shovel thrown in. As I said earlier, some of us had additional things to carry. You have someone right below you, and someone right above you. You have to worry about stepping on someone, and being stepped on, all the while hoping not to get caught up on the rope with the gear that you are carrying. There was no going back, nor any moving ahead of your place on the ladder.

When you reached the landing craft you had to make a quick decision as to how to get into the boat. The boat is going up and down, and the ship is also moving. Between the time that you decide to jump, and the time that you hit the deck the boat could easily move two feet up or down. Keeping your balance while landing was almost impossible. Your only hope was that someone would grab you and help you get out of the way for the next man. There is no time for indecision. One reason that I worried a lot about this maneuver is that it always tested my strength to the limit. But as I began, I don't remember anyone ever getting seriously hurt.

"This is Fiction"

31 March 2000

Dear Nancy,

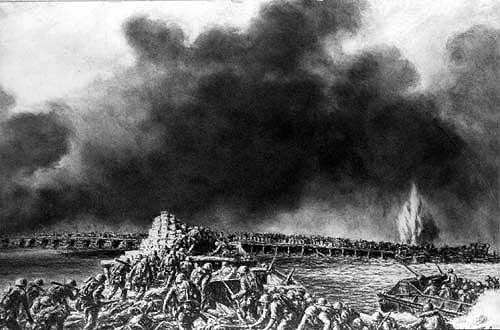

Here is my response on the pier picture. This is fiction. Perhaps an artists attempt to cover three stories in one picture. From the picture, one doesn't know where the beach is or where the ocean is. There is no conceivable explanation for where the landing craft (amtrak) is going, and the structure in the foreground is not anywhere near the pier, if any place. For the life of me I don't know what is on the pier. There was almost nothing the first day. If this is a D+1 story, then the rest of the picture doesn't make sense. The pier looks poorly made and it was not. It was well built, and for peace time service. It was level, and unusable for the most part of D-day. In defense of the artist, he can do it anyway he pleases. My only objection would be that he distorts history, and without an explanation, I'd like to know why.

"A Little Introspection"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

I am enjoying this exercise. It is giving me a chance to reexamine some of the experiences of the war, and to see them in detail never attempted before. I have come to realize that much of what happened at Tarawa, and therefore all of my war experiences were probably seen with tunnel vision. I had never told anyone about the stuck ramp story, because it didn't make sense that there was no one in front of me. Now I know that they were there, and probably setting down. I just didn't notice them. In examining the pier picture I was able to recall things that I had never thought of since they occurred. It has been revealing to me, and rewarding. I am very aware of the frailties of the mind, how we put the parts together to make a whole, and how we never see the "big" picture. Some vets give you the impression that they were on a guided tour. I know that what I saw was very little, and the timing of it will always be questionable. More on this later.

"Pier Picture"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

I will respond to "bullets and barbed wire" shortly, but I have a few more comments on my earlier statements. The pier picture is definitely D+1. If you have a copy of Hammel's "76 Hours," it shows a picture of the top of the pier between the hours of 1300 and 1500. There is no evidence of either supplies or activity on the pier. That is the way I remember it. I would love to see a map of Tarawa with the pier, the amtrak, and the Marine action as it would have been seen from the air. Another small point. The Marines in action on left forefront of the picture are all wearing their back packs. Try and find many pictures of that action of Marines with back packs. That was the second thing we all dropped, the first being our gas masks. The smoke was a first day-mostly pre landing sight. The amtrak bothers me because it had to be going somewhere, and would never have moved parallel to the beach. Too easy a target. Some of the things I am complaining about probably did happen, but basically just don't fit.

"Barbed Wire and Bullets"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

Dear Nancy,

I have a little difficulty with this picture. I did not experience walking across the reef under fire. This is the probably the biggest mistake made, and I don't think that it had to be made. Like most judgments, hindsight is usually better than foresight. The landing of the First Battalion started very early and immediately came under intense fire. I don't know enough to criticize the action, but I am sure that we had other options. It was terrible, however this picture does not depict what happened. These were fresh troops and only saw a relative short time under fire. The looks of the Marine in the picture depicts a man in battle several days, at least. The men killed on this landing were probably tired from being in the boats for a long time, but not in the condition of the Marine portrayed. I recognize the artistic license that artists have, but I am only pointing out things that might be noticed by someone there. Also, I'd question the bayonet being attached, since there was going to be no opposition from the beach, which we held. My first thought was that this was a veteran of two or three days fighting. Other than that, it sure is a good representation of the fatigue, the desperation, and the destructive nature of war.

"From the Beginning"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

My memories of the Tarawa battle are a series of episodes, and none especially worthy of reporting, but I will enumerate many of them for you, and expand when I think it is worth while. You can ask for elaboration when needed.

Just prior to disembarking, in fact the order to fall out on deck preparatory to disembarking had just been given, when a Marine rolling off his bunk, somehow accidentally pulled the pin on a grenade, and it exploded. In this hold the beds were stacked five high, and it was possible to be placed where you could stretch out and touch 45 men. In getting out of the place we always started at the bottom and worked up. The grenadier was in the third level, and I was about 10 feet away in the fifth level, and since we had just been given the order to "fall out," I was just starting to climb down when the explosion took place. I immediately thought that it was a Japanese shell since we had just moved away from some shellfire. Unbelieveably, nobody was killed, and only about 6 or 8 wounded. This story is mentioned in Hammel's" 76 Hours" The version found in the book is a total fabrication. The man was not lazy or slow, he was only taking his turn. He was ahead of me. The reporting party calls himself sergeant, when he was a P.F.C., and says that he was just entering the compartment, when in reality, he was standing at the base of the ladder so that he would be first to get out. So much for some of the things that you will hear.

After the stuck ramp, the next thing that I remember is putting out the pant leg fire, and then climbing up on top of the pier. There was a chicken, maybe 30 feet away scratching for food. I remember thinking that some Marine would have him for dinner. I only remember seeing one other man about six feet in front of me, We were both as low as you can get. There was an explosion and I'll never know how I knew, but I decided that the man was dead. I crawled up to him, and took out his canteen, and had myself a drink. It was about this time that I spotted the TBY over near the edge of the pier, and proceeded to get in the water and start the trek to the beach. In telling this story to a young couple, probably the only time that I had told it, and by request, and with a few drinks, I was surprised when they were repelled by my behavior. In thinking it over, I have asked myself whether they thought that I should have taken his pulse, rendered first aid, or what? My opinion then and now is that I did exactly the right thing.

"End of the First Day"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

After losing the TBY, I proceeded up to the end of the pier, and in a mad dash I scrambled over the top of the pier to the other side, which incidentally was the headquarters of the Second Battalion. I made inquiries, and soon found the radio dugout for the battalion radio team. It was below the sea wall, deeply dug, and well sand bagged. I entered, and offered my services, hardly believing my luck. In very short order I was told that they did not need any help, and would not need any help. Their reasoning was not hard to follow, and to be honest about it, I probably would have had the same thought processes. My problem was that I did not know what a radioman should do when he is without a radio. Since I was probably early on the scene I decided to wait for some leadership, something to happen, perhaps some orders, maybe a radio would turn up, etc.,etc. The idea of going out away, and finding out what was going on not only was unattractive to me, but I would not know what I would do out there. Not a single man from my radio section showed up, and after a while I went over the sea wall and found myself a bomb crater to hide in. At about dusk, I took a short trip to handle a problem that came up, and as I crawled back in my hole I heard a commotion starting up, and as I listened I suddenly realized that my return to the crater had alarmed some people and they were getting ready to make a move on an intruder. I quickly, and loudly spoke up and after that I was very careful how I moved about. Soon after that it was dark, and I went to sleep. More about me and sleeping next time.

"Sleeping"

1 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

Pearl Harbor day, Dec. 7,1941, was the first time that I went to sleep on duty. It was not the last. For some reason I cannot stay awake at night. I do not know if it is physiological, psychological, or in my genes, but I do know that when I am tired and I lay down I go to sleep. I had been up since 2 am and had had a hard day, and by dark I had fallen asleep. I slept so soundly that I missed a Japanese bombing, a Japanese soldier being killed within 30 feet of me, Japanese firing from abandoned Amtrak's, and I don't know what else. What finally awakened me was the Japanese machine guns firing right over my crater at the troops of 1/8. Soon thereafter, our mortars opened up on the Amtrak's, machine guns on the pier opened up on the abandoned landing craft. The day had started. I am not very proud of my sleeping on duty. It is a capital offense, and men have been shot for it. My only defense is that we are all different, and some of us require more rest than others, and none of us can go without sleep for an indefinite period of time. Most drivers have nodded off on occasion while driving. Denying people rest is a form of torture. Finally, the military does not consider rest an important consideration. On Pearl Harbor Day I was given a radio watch, and told to keep it open. Never did anyone suggest that I have any relief. Such commands are unrealistic.

"Pictures"

2 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

Reflecting on what I have been saying, I'd like add a little, and modify a little. I did not go to sleep on watch or on post at Tarawa. I just went to sleep, and I suspect every man there got some sleep, off and on, during the battle. I don't think any of them slept better or longer than I did.

As for the barbed wire, I was not aware that the wire was especially troublesome. I think that most of the D-day forces got through pretty much OK. It was the machine gun fire that forced so many of them into uncleared areas. One of the maps available on Tarawa on the Web has wired approaches indicated. Wire was no problem around the pier when I was there. My destination was Red-3, and it gave me a chance to see Major Crowe under fire again. He never got off his feet! The first day he was seldom more than 30 or 40 feet away from me, and I never saw him on the ground. At times he was down on his haunches, probably to protect whomever he was talking to, and frankly, I wanted to see him get down.

Something that I haven't mentioned is the fighting on the ground. On the first day it is my belief that there was little or no advancement on our sector. That famous concrete building was just a short distance away from Crowe's position. There were too many fortified positions opposing any movement, and most efforts were designed to take out these "little forts" one at a time. (I am not a good witness for this analysis.) We saw the destroyers Ringgold and Dashiel come as close to the shore as possible, and it is hard to believe how much this Naval courage was appreciated. I think that the Captain of the Ringgold got the Navy Cross.

We saw the tank "Colorado" come on the scene, firing away at different gun emplacements. I don't think that anyone there will ever forget the "COLORADO."

Dive bombers (ours) let their bombs loose, and they seemed to be headed directly toward us, and they did pass over us at a very close range, hitting only yards beyond our front lines. The heroism of the front line troops, so much of it unobserved, unappreciated, and unknown is something that we will never be able to properly recognize. At this time I would like to salute them all again.

"Wounded Man"

2 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

Your picture of the wounded man being lifted over the rail does not have much "meat" in it for me. I could be wrong on this, but I think that my experience involved the Amtrak being lifted up to deck level, and I was able to walk to the hospital area. Interestingly, My foot was exrayed, but only looked at about a week later. My foot was found to be fractured and when we got to Hawaii I was lifted off the ship with an identical gurney.

This is a story that I have to tell you. When it became time for me to be shipped back to the states, I was wheeled into the medical room to have a cast put on my foot. The doctor examined the wound, and asked if the shrapnel had been removed. When told that it had not been removed he called for a scalpel, and proceeded to probe and to dig for the little pieces in the bottom of my foot. No anesthetic! I would love to tell you my thoughts about this time, but it is against the law. Suffice it to say that I could have killed him. However, he being Navy, and I not, I didn't say a word. I am still talking to him mentally, and will as long as I live.

"Second Day"

2 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

On the second day, to a certain extent, it was more of the same. The pier had been loaded during the night, and the struggle to eliminate pockets of resistance continued. The beating that the troops of 1/8 were taking was not obvious to many of us on shore. All the time the Japanese machine guns were firing at 1/8, I had to keep my head down because the bullets were actually going over my head. I could see the mortarmen firing at the abandoned Amtrak's, and I got a glimpse of the efforts to subdue the Japanese snipers on the old beached freighter. Later that day I saw a very brave man on a bulldozer pushing dirt into the entrance of the two story, concrete headquarters building. Why he wasn't picked off, I don't know. As for myself, a few members of the radio section had found 2/8 headquarters, and with a few others we moved out onto the airfield, dug in a little bit in preparation for an anticipated Banzi attack that night. I had fired my carbine a few times to clean out the barrel by firing into the tops of the coconut trees. This was a habit that I had picked up in Guadalcanal. I had no other targets. Again I turned in early, and had a good nights rest. End of day two. In retrospect, I do not remember very much about day two. I don't remember being bored, or time dragging, but at the same time I certainly was not involved in much productive work. At this time it is hard to understand how I could remember so little.

"Upon reflection...."

3 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

I have a few comments that are, perhaps, not relevant to your work, but I want to say them anyway. This effort on your part to elicit WW2 memories from me has been possible only because I don't know you. Also very important to the process was the fact that you asked for help, and indicated an academic pursuit was involved. Without these elements, I don't think that it could have happened. It has been a rewarding experience for me. I have not been particularly interested in the "facts" of the war, but I have always been interested in the men who shared the experience. When we get together, we usually have a barrel of laughs, and are made aware of the lifelong bond that we made so many years ago. We do not talk of the bad parts of the war.

In reviewing my time on Tarawa, I have had a second insight. For some time I have had trouble figuring out where Eric Hammel got his 76 hours, but I haven't been interested enough to read his account of the battle. In trying to recall the third day of the battle, I got his book out, and lo and behold, he is right. I have lost a day somewhere. Incidentally, I may have confused some of the events that I thought occurred on the second day with the third day. There is one nights sleep that I am sure that I had, but cannot remember. In trying to figure out what happened, I suddenly realized that I could remember the first few hours almost minute by minute, but as time passed my memory got dimmer and dimmer. I have lost a whole day. I do remember walking around on the last day after the fighting in my area was all over, and I gather the Colorado was on the third day.

I know that memory is reinforced by the extremes. We remember firsts, lasts, biggest, smallest, coldest, hottest, etc.. I think that repetition, fatigue, and other factors, perhaps emotion, tend to diminish our long term memories. If what I think is true, then perhaps all war time memories should be weighed in terms of when they occurred, and under what conditions. I think that maybe I should end the tale here, and of course, if you have any questions just send them to me.

"Not much Subject"

3 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

On the fourth day around noon, men began to stand up, and slowly started to look around. The little firing that I heard was from a distance. We were soon looking for something to remember the place by. ( It has been referred to as souvenir hunting.) I remember seeing many suicides. Men with their toes in the trigger guard. There were many dead Marines around. In one dugout that I went into (fool that I was) one Japanese soldier was, I thought, dead, even though he was losing blood from a wound to the side of his abdomen. Later TV shows told me that you can't bleed when the heart stops. I do not remember much emotional feeling at the time. I think being alive was was what it was all about. Also, when you are stressed out over a protracted period of time, your emotions are dull and numb. I don't remember any show of happiness.

Within an hour the battalion CO had us rounded up someway, we boarded a landing craft and shipped over to the adjacent island where we spent the night. I remember the cleanliness of the air, and the freshness of a cool breeze. It was a very appreciated change of pace. Next morning we boarded ship and went to Hawaii. I have a copy of Sherrod's book, signed by both Smith and Shoup, and I have browsed through it, and read some parts in detail, but I don't think that I have read any WW2 history in it's entirety. In my mind there are two historical records of important events, one objective (historians), and the other subjective (participants). Each has an important role to play, and of course, anyone can play the historical role, and I do not deny it's importance. In one sense, the historian can weigh, measure, count, time, compare in terms that have a solid foundation in fact. The other is most often a judgment, a memory, a feeling, an attitude, and sometimes only a single witness. It is often an area of questionable opinion, but for some reason, it is the only aspect of WW2 that I really care about. I think that it is the ultimate bonding of men. I do not remember the smell, but I know that it was there. As for the island rocking-I'd say shake, rattle and roll would be a more accurate description. Yes, you could feel the bombing and the other explosions. In a way you seem to suggest more mental evaluation, more introspection, and perhaps more objectivity than I think that most of us had. This was not a philosophical exercise. We were not setting back saying to ourselves, Hey, what do you think about that? I think that most of our energies were spent trying to stay alive and do a job. For most of us it was about all that we could handle.

"Post Tarawa"

4 April 2000

Dear Nancy,

I am sure that what I am telling you is not always clear--even to me. However, there is no connection between bonding, and anything that I had to say about subjectivity. Bonding is the unexpected outcome of the shared experience. For many of us it was unreal until we started to make contact with our former war buddies. We were hugging, choking up, and for some, crying. I don't think that most of us knew it was there. You raised the question about keeping in contact. As I said, we did, and we do. My buddy named his son after me. His first name being Tilghman, was never in consideration when I named my boys. On the odds factor, yes it is there. Something that I remember very clearly is when we went into Guadalcanal, I did not want to get hit. I wanted nothing to penetrate my skin. When approaching Tarawa I decided that I'd settle for a leg or arm wound. By the time Saipan was nearing I decided that I would be willing to lose a leg or an arm. In thinking about my greatest fear the night before the Saipan landing, and the subsequent action the next morning, I have concluded that I was probably just as good a Marine, perhaps a better fighting man than earlier in the war, but very conscious of the possibility of dying. That possibility did not reduce my effectiveness. As I stated earlier, the most dangerous situations were not the most frightening ones. That is probably hard to understand. My thinking is that the mind, if occupied with something to do, doesn't have time for reflection on the nearness of death.

* All drawings should be credited to Kerr Eby - Navy Combat Art Collection

Les Groshong spent three years with 3/HQ/8 as a radioman. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve on 10/04/39 and was called to active duty on 12 November 1940. He was discharged as Radio Chief on 9/15/45. Les was at Guadalcanal from 11/4/42 till 2/8/43. He landed on Tarawa on 11/20/43 and left on 24 November. At Saipan Les was wounded in action during the initial landing 15 June 1944. On 15 June 1945 he was discharged as Radio Chief.

Radio Section 3-HQ-8 at Guadalcanal

The lines behind the group are telephone lines.

| Front Row: | Back Row: |

| John April | George Kern (KIA Tarawa) |

| Kenneth J. Connor | Carl Schroeder (nicknamed "pop") |

| Ralph Sharkey | T.C. Smith (WIA Saipan) |

| James L. Bennett (KIA Saipan) | Donald Pettibone |

| Les Groshong (WIA Saipan) |

Read more by Les Groshong: Going Home: One Flag's Long Journey

Visit Les Groshong's Website.

copyright 2000 Wheaton, Illinois

Created 20 October 2000 - Updated 4 July 2003

Return to Index