by Les Groshong 3/HQ/8

with Jonathan Stevens

I hope that this is not the last chapter of this story. It has been over fifty-seven years since this story began, but my memory of most of the details are still firmly held in my mind, even though my short term memory has been harshly treated by the aging process. Hopefully, this story of the capture, if you can call it that, and the attempt to return a Japanese flag to it's rightful place, will encourage others to consider the merits of doing the same.

In early January 1943, my outfit, 3-HQ-8, 2nd Marine Division, was on the front lines, on the beach at Point Cruz, Guadalcanal. The decision had been made to start the final push to end the diminished Japanese resistance on the island. On January 10th, after an extensive artillery barrage, the infantry companies moved forward against moderate resistance, and after advancing about a thousand yards, they paused to secure the advancement. About this time, six American light tanks came up the road from the rear, approached, and then crossed the old front line area. As soon as they passed this point they spread out and commenced firing. They hit a lot of trees, and a lot of bushes, but unfortunately they also hit some of the men who had made the earlier advancement.

The scene that immediately followed has not diminished in my mind with the passage of time. Major "Jim" Crowe, whose presence near the battalion headquarters was unknown to me, immediately became resoundingly evident to everyone anywhere near that spot. He unleashed a roar that defies description and charged one of the tanks. The Major grabbed an outside microphone, and with words, perhaps unspeakable language is a better description, gave unmistakable orders. The tanks, it seemed to me put their tails between their legs like dogs, bowed their heads, and as they say, turned tail and ran. Such was the power of the Majors' personality.

Shortly after this incident occurred, Major Crowe called for volunteers to be stretcher bearers, and Corporal Elmer Stone, the battalion interpreter, and I, Les Groshong, radioman, grabbed a stretcher and moved forward. Soon, we were bobbing, weaving, and crouching down. With the sporadic rifle and machine gun fire, the situation was less than comfortable. As we were moving forward, we could see the line troops, hiding behind stumps, and fallen trees, and hugging the ground. I had the feeling that they knew what they were doing and I knew that we did not. It took longer than I would have preferred, but finally someone pointed in a specific direction, and soon we came upon an Army soldier on his back. He was neither moving nor bleeding. I assume that the Americal Division had an observer or two with the advancing troops to get the feel of the situation, and this man was probably their first casualty. We were told to take him to the aid station, and I responded by saying, "It's no use, he is dead." We were then directed to put him in a shady place by the side of the road. Later, I had to ask myself how I was qualified to make such a judgment.

The next day, when things had quieted down, I decided to go forward again to see where I had been, and perhaps keep my eyes open for something to remember the place by. This quest has a name that isn't always seen in it's proper light. Some people look down on "souvenir hunting" but only because they do not understand the intricacies of the art. Care must always be taken, because booby traps are a very real concern. The beginner will often pick up things that are too heavy to carry far, too fragile to endure the weather elements, too small to ever impress anyone, etc., etc. Some things, swords for instance, require constant vigilance, and must be carried on the person at all times. Souvenir hunting is truly an art, and should be appreciated as such. Besides it was the only form of entertainment available.

Anyway, off I went to the new front. Things seemed to be very relaxed with men milling around. For some time now the Japanese were reluctant to fire on easy targets, because of the massive retaliation they would receive. Often, one shot by them would trigger an artillery barrage or mortar attack, and the men on the front would take the opportunity to clean their barrels. It wasn't a good exchange for the Japanese soldiers. We had the fire power and they did not.

Shortly after arriving at the front, and while examining the damage to a bombed out bunker, I noticed a brown expanse of skin-like material at the bottom of this ten foot deep hole. Further inspection revealed it to be the small waist area of a man's back, and it seemed to be alive. I called out to others that there seemed to be a live Japanese soldier in this hole. He was mostly covered by debris, but others soon gathered and confirmed my suspicions. Soon a discussion started concerning what course to take. The first words that I heard were "shoot him," and then "don't shoot him." As the debate spread and grew in volume, I decided not to be involved, and prudently backed off. Finally, reason reigned, and an effort to rescue the man was started. Later that day I saw him being interrogated.

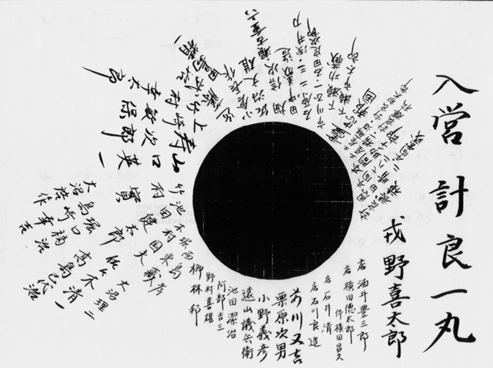

It was only a few minutes later that I found an unopened Japanese backpack. Inside was the flag pictured with this article. It was very dirty, had a knot tied on one end, and had many Japanese characters all over the front of it. At the time I would have preferred a new, clean, and neatly folded flag. I believe that if I had found one in better condition later on I would have thrown that one away. Flags make an ideal "find" because they are not damaged by water, they are light weight, and they make a good display. Hence, regardless of the condition, this flag was a good find.

A few days later fortune again smiled on me. For the first time in over a year we were told that we could tell family and friends where we were and we could send a package home. I can only assume that our planned departure to New Zealand had been a factor in this decision. I took the opportunity to send the flag, and two .25 caliber bullets home to my parents. A few months later I received a letter from my folks, and included with it was a picture of the flag and two bullets being displayed in a J.C.Penny window on the main street of my home town. This was probably the first Japanese battle flag seen by the home town folks.

My guess is that I never again gave the flag a thought until I got back home in July of 1944, and beyond getting it out of the plastic bag that it was in, and looking at it a few times over the years, I never showed it to anyone. It was only when I started to dispose of some of my accumulation of mementos, souvenirs, whatnots, and other items that no longer meant much to me, and more importantly, would not mean much to my children, did I give any thought to the flag. The disposal started with some pictures that I had of American Samoa.

I was in the used book business for over forty years and during that time I was fortunate enough to have met many people from many places. One was an American woman who had married a Samoan and lived in Samoa. Having spent nine months in Samoa, I was pleased to have the opportunity to talk to her. In the course of the conversation, she told me about the museum that they now had there, and I told her about some pictures that I had of the people, and the island. She thought that the museum would be interested in seeing the pictures, and gave me the museum's address. I mailed the pictures, and received a letter of appreciation from the director, who said that of the 35 pictures I had sent, only one was a duplicate of their collection. I was very pleased to know that the pictures were going to be of some value to this museum.

I must mention my next rewarding donation. While home on leave, after being wounded on Saipan, I receive a call from a Boy Scout official, who informed me that I only lacked one merit badge in swimming to complete the requirement for Eagle Scout. I met the requirement, and in a Marine uniform (with a hash mark), I was awarded the Eagle Scout badge. Scouts Honor! Some twenty years later I gave all my Scout memorabilia to a Scout leader who made a glass covered case for the collection of scouting materials that I had. Now my children will not have to say, "What do we do with this stuff?"

At a later date I met Reggie Ikebe (ick-eh-buh). We had had discussions on v various topics before I found out that he was from my home town, and that I had gone to school with his aunt. Over a few years we had become well enough acquainted that when he told me that his parents were going to Japan, I quickly thought of the flag collecting dust in my closet. He was sure that they would be pleased to return the flag to Japan, and that is what they did.

About a month later Reggie showed up at the shop with a letter written in Japanese, a picture of the flag being held by Reggie's mother, father, his cousin, and three other friends. Also, there was a form with my business card, along with other notations in Japanese. I was pleased, and impressed, however not being literate in Japanese I did not ask for copies of the documents. And that seemingly was the end of that disposal.

Years later, when in communication with Jonathan Stevens, (the creator of "Tarawa on the Web"), concerning his offer of a copy of his father's maps of the Tarawa battleground, I declined indicating that I was in the process of disposing of many of my WW2 momentos, papers, etc. In fact, I had given away a pre-battle map of Betio Island showing the Japanese defensive positions on the island. I also mentioned that I had returned a Japanese battle flag to Japan. Jon, always looking for a story, suggested that the flag story might be worth writing about, and offered his assistance if I would be willing to tell the story. I gave it some thought (about a minute), and decided that I would do it if I could get more information on the flag's history since its return.

My first task was locating Reggie Ikebe and getting copies of the original documents, if he still had them. I had moved from California five years earlier and lost contact with Reggie. But with the help of my computer, and a few phone calls, I located Reggie and we were soon talking old times. I asked about the documents concerning the flag and he thought that his mother still had the letter and the picture. Only a few days later both documents arrived by mail and I immediately began thinking about getting them translated.

The only translator that I ever knew was Elmer Stone, and he was so right for the job since he was on the scene when I found the flag. Suddenly my imagination took over. Perhaps the flag belonged to the man captured that day I found the flag or at least he knew the owner. Again, maybe Elmer would remember something that would tie it all together, especially if Elmer was the interrogator of the prisoner. Wow! Such thoughts compelled me to e-mail Elmer, to outline my problem, and to ask for his assistance. To impress him I threw some Latin in (pro bono) and he graciously agreed.

Here I think a few words about Elmer Stone are in order. When I knew him he was a corporal, but soon after arriving in New Zealand, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant, and was a Major by the time he left the Marine Corps. He then went to law school, graduated, opened his own law offices, and later joined an international law firm. He spent many years opening law offices in the far east. Beyond that, all I know for sure is that he was a damned good corporal.

A few weeks after my request, the English translation arrived. It turns out that the flag had not been returned to its home town as I had thought. Translations between the Japanese language and English are sometimes imprecise, or so I am told, and can result in misunderstandings like this. However, much interesting information had come to light from the translation of the papers the Ikebe family gave me. The writing on the flag was determined to contain fifty-one names, with one name, "Keira," appearing three times. This suggested that the original owner of the flag probably was himself a Keira, a rather rare name, known mostly in Southern Kyushu or Okinawa. Knowing that the flag would be "precious and priceless" to the families named on the flag, the Ikebe relations in Japan decided that they would try to locate the family of this soldier named Keira.

Upon hearing of my interest in the status of the flag Mrs. Ikebe, (Reggie's mother) wrote to her relatives in Japan asking for an update. Her family wrote back that they had been unsuccessful in locating the right Keira family. They ultimately decided to turn the flag over to a newspaperman, whose resources and contacts were thought to be sufficient to do the job. Now, so much time has passed that they are no longer in touch with the reporter, and at this time they are unsure of the whereabouts of the flag. She is hoping for more information later. So am I.

In a way I am disappointed that everything did not turn out peaches and cream. Yet, in another way I am glad. My next step will be to contact the Japan Times which is the largest English language newspaper in Japan. With their help I hope to locate the flag, to find the correct Keira family, and set the record straight. Hopefully, in the long run, my effort will give some impetus to return other flags found on the numerous Pacific battlefields to the families of Japanese soldiers killed in the Second World War. So again I say, "I hope that this is not the last chapter of this story."

Read more by Les Groshong: An Interview

Email - Jonathan.E.Stevens@wheaton.edu

copyright 2001 Wheaton, Illinois

Created 1 September 2001

Return to Index

Return to the 2nd Division in the Solomon Islands